Tapas Chandra Roy talks to Anoushka Rabha about the challenges of millet cultivation at the grassroots level, the Odisha Millet Mission, and sustainable farm-to-plate models.

Tapas Chandra Roy has left no part of his life untouched by his passion for promoting millets in the modern-day diet. As a certified farm advisor, agricultural officer, author and blogger, and a dedicated cook too, he uses every opportunity to popularise millets—by consulting with farmers and agricultural agencies, and writing about these ancient grains.

Over the years, he has been instrumental to the Odisha Millet Mission (OMM). OMM aims to improve millet production and local consumption and facilitate the procurement and distribution of regional millets in Odisha. Roy has also worked on drafting a White Paper on millets, which sought to understand India’s complex millet ecosystem and the challenges faced by dry-land millet farmers.

His experiments in cooking with millets are varied, with videos on his Youtube channel including recipes for kodo idlis, ragi laddoos, proso pongal, and even a browntop porridge.

Ragi Rasgullas with Jaggery that Tapas Chandra Roy made as a treat for his birthday, which ended up winning an award in a cooking contest!

What inspired you to focus on millets as a core part of your work?

I work largely with farmers from the Paraja tribe, and many of them grow millets. Initially, I didn’t have much knowledge about millets, but I wanted to serve these farmers better, so I started learning about the grains in 2013. From then on, I took various courses, and attended workshops and training programmes. In 2017-18, I took the Certified Farm Advisor course introduced by MANAGE in collaboration with the Indian Institute of Millet Research. The institutions and farmers I worked with inspired me, helping me understand how to assist them better. It is what keeps me going.

Could you give our readers more context about the Odisha Millet Mission and its goals?

The Odisha Millet Mission is an initiative aimed at helping small and marginal tribal millet farmers. When it began in 2017-18, the main objectives were to increase yields, promote the consumption of millets by 25 percent, and include millets in programmes like the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) and mid-day meal schemes.

It also focused on improving processing through Self Help Groups (SHGs) and Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs), and diversifying cropping patterns. Over time, we also worked on commercialising millets and ensuring farmers received the right prices for their produce. We’ve made significant progress, especially in regions like Koraput, where millet cultivation has expanded significantly.

Another focus is on conserving landraces of millets, like the Kundra Bati, Laxmipur Kalia, Malyabanta Mami, and Gupteswar Bharati, which are all notified varieties of millets within the Koraput and Malkangiri districts of Odisha. The Bhumia tribe has conserved and grown the Kundra Bati for a hundred years now, and we are in the process of getting a Geographical Indication (GI) tag for it.

[A landrace is an often local, domesticated species of plant or animal that has not been affected by modern breeding practices, but improved over time by physical selection for ecological suitability or culinary uniqueness like aroma or taste.]

How do the people of Odisha view millets? Have they always been part of the diet here?

Traditionally, millets have been more commonly consumed among tribal populations in Odisha. However, in the last seven to eight years, there’s been growing awareness and popularity of millets amongst urban consumers. The demand for millet-based products in cafés is also on the rise. These developments have been driven by efforts like the Odisha Millet Mission. For the tribal communities, though, millets like mandia or ragi (finger millet), have always been a staple.

[Read more about Tapas Chandra Roy’s study of finger millet recipes of Odisha’s Tribal communities here, and find a recipe for mandia pej—a probiotic drink popular across Odisha—here.]

Women’s Self Help Groups (SHGs) in Odisha have played a key role in promoting millet-based products. How do they contribute to the millet value chain and the economic empowerment of women?

Many women who were once hesitant to leave their homes are now leading groups, running businesses, and innovating with millet-based products. These groups, like Maa Thakurani Kalanjiyam SHG, have not only promoted millets at the village level but have also helped create value-added products that have found success in markets in urban areas. Their involvement has empowered women economically, and they continue to play a crucial role in the millet value chain.

Many women who were once hesitant to leave their homes are now leading groups, running businesses, and innovating with millet-based products.

[Read more about women’s SHGs in Odisha in our excerpt, Flour Power: Women-led Millet Value Chains Improve Local Nutrition, here.]

Could you describe the challenges you encountered while implementing the Odisha Millet Mission at the grassroots level?

The Odisha Millet Mission was introduced in 2017-18, initially in a few districts such as Koraput, which produces about a third of the state’s millet output. At first, we had a limited budget and targeted a smaller number of farmers. Convincing farmers to adopt better agricultural practices was challenging, as many were hesitant to change. We introduced the System of Millet Intensification (SMI), but many farmers were skeptical at first, especially when we showed them how to transplant millet seedlings—something they had never done before. However, once we showed them the improved yields for finger millet—up to six to eight quintals per acre, compared to the two to three quintals they were getting before—they began to come on board. The government’s support in procuring their produce at the Minimum Support Price (MSP) was also crucial. In 2024-25, the MSP for finger millet is rupees 4,290 per quintal, which the state government supported with an additional rupees 210 to bring it to rupees 4,500.

[Watch a video describing the System of Millet Intensification created by the Odisha Millets Mission to train farmers, here, and read more about the Odisha Millets Mission, here.]

What about post-harvest processing? What challenges do millet farmers face, and how can these hurdles be overcome to ensure profitability and sustainability?

Post-harvest processing is one of the biggest challenges for millet farmers. Many don’t have access to proper processing machines, especially for minor millets, which are difficult to process. Even with little millet, the recovery rate is only around 65-70 percent. Decentralised processing units at the village level would help a lot. Farmers also need better market links to ensure they receive fair prices. The Odisha Millet Mission is working on fixing benchmark prices for minor millets like little millet and foxtail millet to ensure that farmers are incentivised to grow them.

As a member of the Task Force for the White Paper on Millets, what were the most pressing policy recommendations you contributed? How do you think these will shape the future of millet farming in India?

One of the key recommendations I made for the White Paper on Millets pertained to seed quality. While some varieties like finger millet and sorghum are easy to find, minor millets require more support in terms of seed production and distribution. Another issue is incentivising millet farmers. Though growing millets requires fewer resources, farmers, especially those growing minor millets, struggle to receive adequate support. We also need to focus on increasing millet consumption and expanding millet farming to other states through policy changes. The support system for millet farmers is crucial, and there’s still a long way to go.

Could you tell us more about how finger millet, in particular, has been utilised for nutritional security in your projects?

In 2017-18, I conducted a study on finger millet and how it contributes to nutritional security. I focused on understanding the challenges in processing, seed quality, and farmers’ perceptions. A key finding was that to increase millet consumption, we needed to introduce it into mid-day meal programmes because the younger generation isn’t as familiar with millets. Another concern was year-round availability. We noticed that after July, the availability of finger millet decreased, compelling people to buy it at higher prices. This is something we’re trying to address by supporting processing at the local level.

A key finding was that to increase millet consumption, we needed to introduce it into mid-day meal programmes because the younger generation isn’t as familiar with millets.

You’ve mentioned the importance of connecting millet production on farms with increasing consumer demand in urban areas. How do you create a successful farm-to-plate model?

Connecting the dots between farm production and urban demand requires awareness and education, especially in urban areas. Social media has played a big role in educating people about the health benefits of millets. The International Year of Millets in 2023 also helped raise awareness globally. However, more support is needed at the policy level to continue promoting millets, and we need to ensure that consumers understand the value of incorporating millets into their diets.

Water scarcity is a major issue in agriculture. How do millets fit into the context of water scarcity, and how resilient are they?

Millets are incredibly resilient, especially in regions with low rainfall, like Rajasthan. Millets, particularly pearl millet, can thrive with as little as 350 to 450 millimetres of rainfall. In areas with water scarcity, millets can be a lifeline. They also help prevent soil erosion in hilly areas like Koraput and Assam. As climate change continues to impact agriculture, millets are one of the most resilient crops and will be essential for future food security.

How do you strike a balance between promoting millet production and ensuring biodiversity in agricultural ecosystems?

Millets are part of the traditional cropping systems in tribal areas like Koraput, and they naturally promote biodiversity. We’ve worked on conserving landraces of millets, reintroducing lost varieties into the seed chain, and conducting biodiversity trials. In these trials, we look at how millets perform alongside other crops like pulses. This helps maintain biodiversity while improving soil health and promoting sustainable agriculture.

Do you think there’s a need for more accessible learning resources to promote millets among larger populations?

Absolutely. There’s a need for more knowledge-sharing platforms, which is why I started Millet Advisor recently.

It has received over 200,000 visitors in 2024 alone! People from all over the world have reached out to learn more about millets, so I think there’s room for more resources.

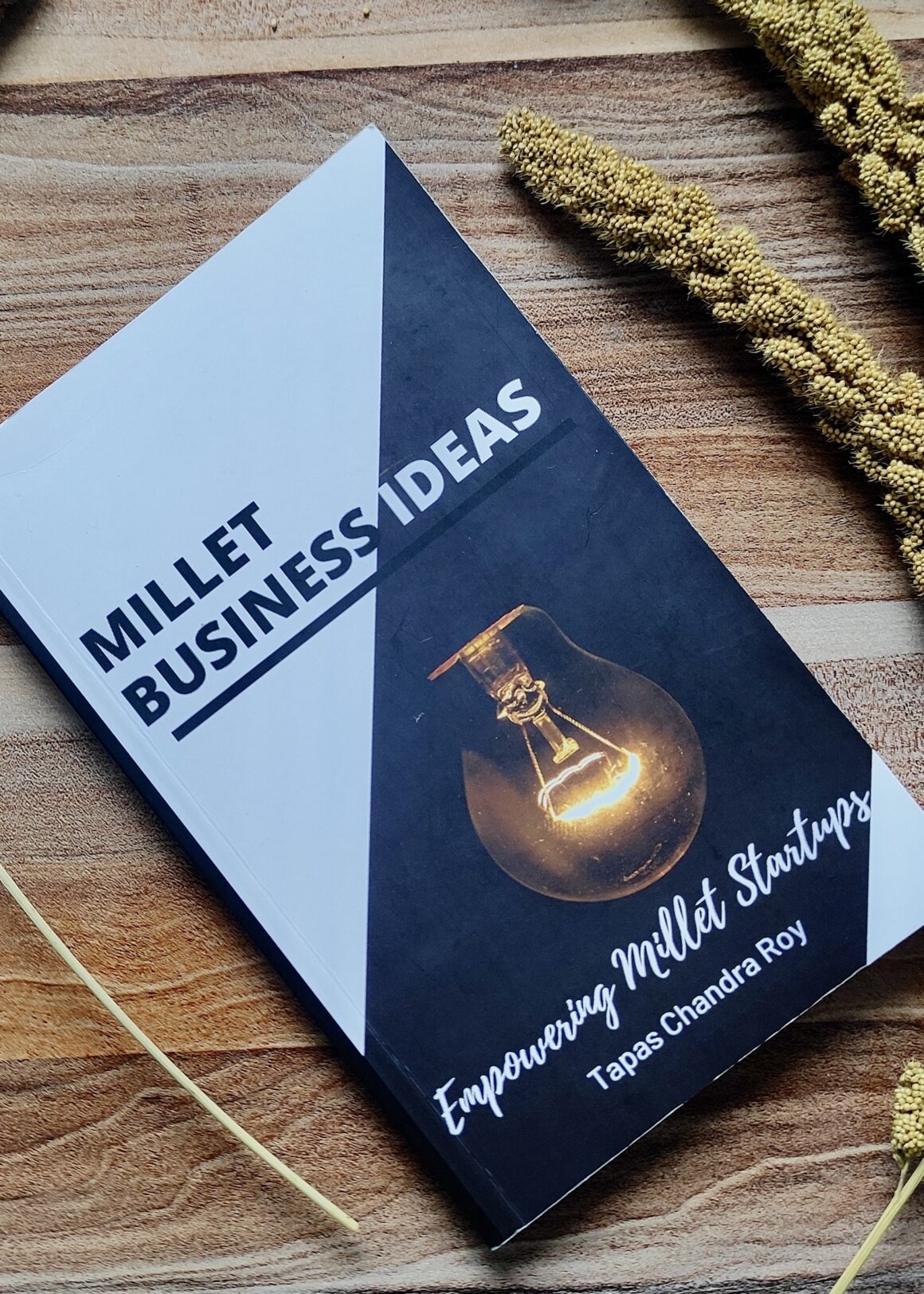

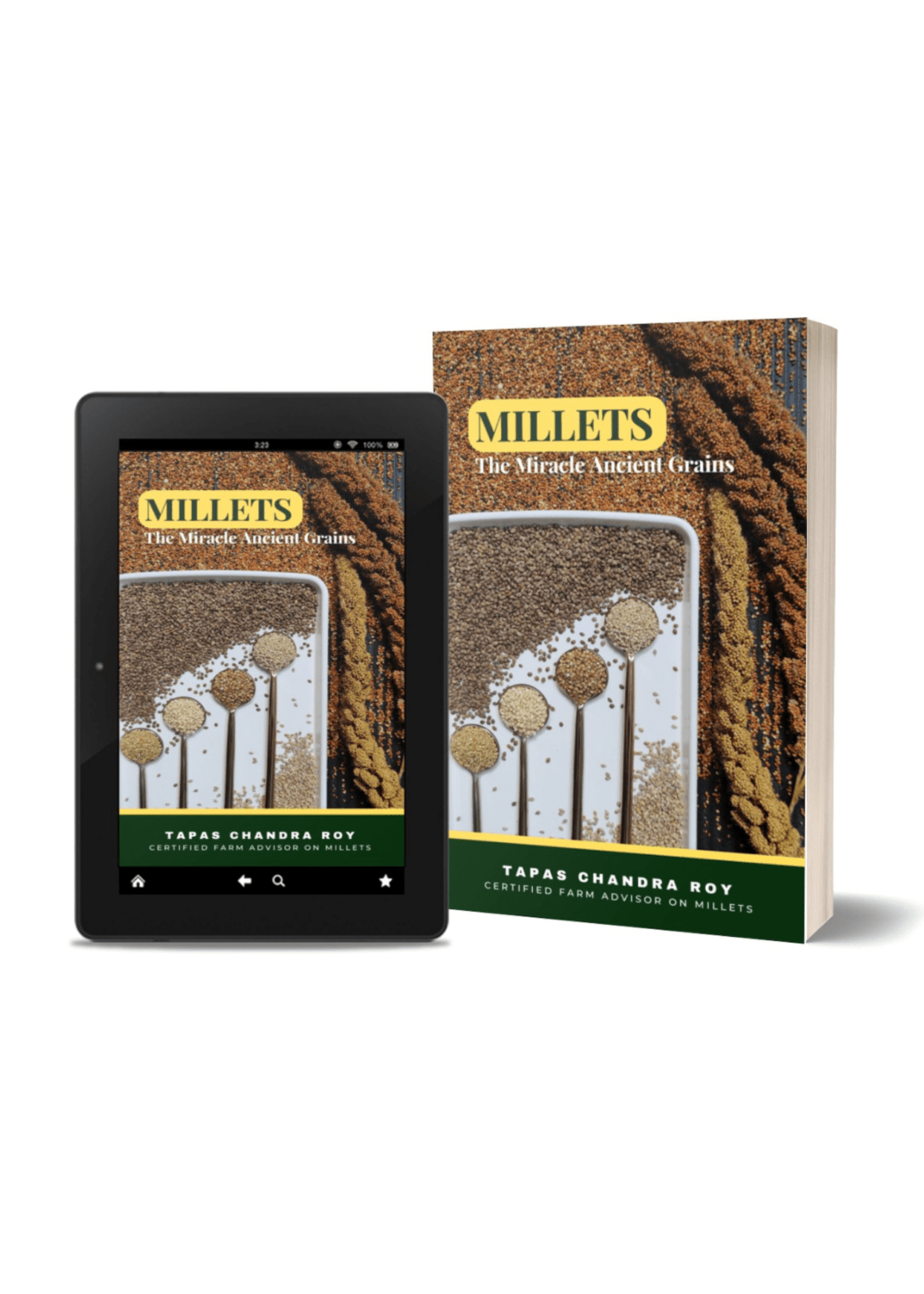

Books authored by Tapas Chandra Roy, researched and written after years of working with millets.

Anoushka Rabha is a volunteer with the Climate and Policy Lab at the Millet Revival Project.

This article is part of the Millet Revival Project 2023, The Locavore’s modest attempt to demystify cooking with millets, and learn the impact that it has on our ecology. This initiative, in association with Rainmatter Foundation, aims to facilitate the gradual incorporation of millets into our diets, as well as create a space for meaningful conversation and engagement so that we can tap into the resilience of millets while also rediscovering its taste.

Rainmatter Foundation is a non-profit organisation that supports organisations and projects for climate action, a healthier environment, and livelihoods associated with them. The foundation and The Locavore have co-created this Millet Revival Project for a millet-climate outreach campaign for urban consumers. To learn more about the foundation and the other organisations they support, click here.