Professor and scientist Dr. Ruth DeFries talks to the Millet Revival Project about the irony of millets becoming all the rage in urban areas in India, while being non-aspirational and stigmatised in rural pockets, and why farmers are still not reaping the benefits of growing them.

Ruth DeFries is all smiles in New York when we get on a video call with her to talk about the landscape that has held her in thrall for decades now. The more time she spends in the forests of central India, the richer it appears, each visit leaving her further amazed.

Located in the Satpura mountain range, the Kanha-Pench forests of central India are both a critical conservation zone and a vulnerable hotspot for climate change impacts, making it a region that aligns with Dr. DeFries’ research goals, which look towards finding realistic pathways for people and nature to thrive together.

In 2014, Dr. DeFries founded the Network for Conserving Central India (NCCI) with funds from the MacArthur Foundation that were awarded to her in 2007, for her work as an environmental geographer.

NCCI’s vision is one of jugalbandi, a harmonising of people and place. It brings together local populations, researchers, managers—people working in the landscape—to think about what the important issues plaguing them are, and work towards resilience for all. “I think anyone who spends time on the ground in India,” Dr. DeFries says, “knows that there is no such thing as conservation without people.”

Our conversation is peppered with a rare awareness from Dr. DeFries of the place she inhabits within this work, despite the many accolades that have come her way. “I’m very cognisant of being the foreigner who comes in with all the answers. I certainly do not have all the answers.”

“I think anyone who spends time on the ground in India,” Dr. DeFries says, “knows that there is no such thing as conservation without people.”

But she does have some—research findings about a variety of millets, things she has heard about whether people still consume and grow them, and what kind of diversity we need for a resilient future.

Edited excerpts of our interview with Dr. DeFries:

Let’s start with one of our favourite questions: what millets do you like to eat? What ways do you like to eat them?

I eat kutki even when I’m in the US; I order it online, though it’s super expensive. I think my favourite way to eat it is just plain kutki rice, with dal and sabji. People do make laddoos and kheer with it too, and the kheer is very good.

(L) Kutki, or little millet laddoos. (R) Kutki kheer, made by cooking kutki in ghee, jaggery, and milk, topped with raisins, cashews, and makhana. Photo (L) by Bhumika Yadav, Greenhub (R) Urvara Krsi.

What has the NCCI’s (Network for Conserving Central India) experience been while working with local communities, through the push and pull of conservation and development?

I don’t want to make it sound like I know everything, or that I can speak for the people, because I can’t. There is a tendency to over-romanticise tribal populations—the Gonds, the Baigas—which I really try to guard against because people are living their lives and trying to make a go of it in a very hard economic and ecological environment.

What’s really important is that people have options—that they have agency and decide for themselves what best suits their passions, their talents, and the situation. So, if they have aspirations to be farmers, make it possible to be farmers: access to market, access to technology, access to a decent way of life.

Or if they want to go to the city, they don’t have to do that out of desperation. There’s a lot of seasonal migration in this region. The goal of development is for people, whether indigenous or not, to have agency over their lives.

And how does NCCI support local partner organisations and communities when it comes to millets?

The work with non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in Madhya Pradesh is about working with them on their interventions with farmers [in order] to increase production and consumption, and to create markets around millets that are grown in that region. Our goal is to look at how effective those interventions are—are farmers using better seed varieties? How is technology reducing labour and improving millet quality? Is it improving incomes? What are the issues that farmers are facing? Are they consuming millets? What are the trends over time?

Because NGOs are busy on the ground, they can’t do this kind of long-term data collection—comparing places where they’re working with other places, to see what the trends are. We call it last mile effectiveness, but people also call it MEL: monitoring, evaluation, and learning.

The market, trends, and consumption patterns are all always changing. So how do places where the NGOs work differ from those that are otherwise the same, except for they don’t have these interventions?

What has emerged from this is that there are particular locations where people have (within very small geographies) very different attitudes about millets—about what farmers want to do, the consumption patterns, how much millets people are currently consuming, whether they want to consume millets at all.

So we’ve been able to parse out that geographic variation, which helps NGOs see where their efforts can be most targeted and effective.

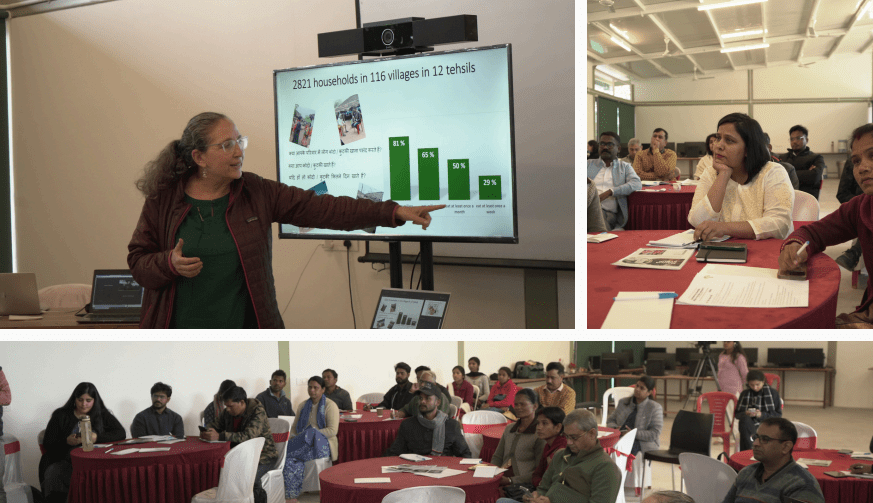

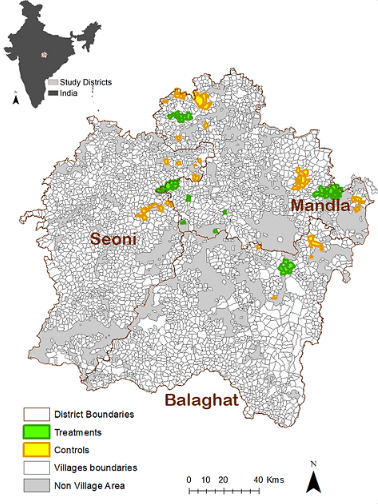

(L) Dr. DeFries and stakeholders from NCCI at the Agrobiodiversity Roundtable held in January 2024, that focused on millets in the Kanha landscape. (R) Areas within study districts in Madhya Pradesh where interventions around improving millet varieties and consumption were made, versus control areas where no interventions happened. Photos by Bhumika Yadav, Greenhub. Map courtesy of NCCI.

You were talking about consumption trends—a lot of it is based on social factors, including peoples’ attitude to millets, but also ecological factors like soil and weather patterns. Can you tell us more about these factors in this particular landscape?

Well, it’s both. We can have a long discussion about millets, and there’s a lot of literature about millets being stigmatised as famine foods, as not aspirational foods. It’s quite ironic that in urban areas, millets are all the rage, and then they have this sort of stigma to them in some rural places. So there is that social aspect—a long legacy of white rice as the aspirational food. We hear that a lot. But we also hear that millets are quite expensive now, even if local people wanted to consume them.

Ecologically, these particular millets—kodo and kutki—that grow well in this region, grow on sloping land. Land where the water can drain, because they can’t withstand too much of it. So within this geography, parts which are hillier and have more of that sloping land, will have millets growing, and then the flat areas will have paddy. All of these millets are rainfed, and from what we hear, they really have no inputs—no fertilisers, no irrigation.

Is it fair to say that millets are more climate-resilient than other grains?

It is very fair to say that millets require less water, and that they are more drought-tolerant, or heat-tolerant, because they are losing less water.

Now, what’s happening with the monsoon is that we’re seeing shorter periods of intense rainfall. And though it’s very hard to predict the monsoon, the projection is that there will be higher total monsoon rainfall, but in a more erratic pattern—short, intense periods of rainfall, then dry spells—and that is actually what we’re seeing. The millets are tolerant to those dry spells, but the intense rainfall? I don’t know.

We did an analysis using historical yield data that is available back to the 1960s, for the major millets (sorghum, pearl millet, and finger millet) because that data is available. It’s a lot harder to get data on these smaller millets because they’re harder to process, and they haven’t been in the mainstream as much. So although all of them have declined, the small millets haven’t gotten the same kind of attention. That’s something I want to look into.

You have been working in this landscape for a while now; I’m sure you’ve seen if there has been a kind of degradation induced by climate change. How has this impacted people, especially with respect to farming and migration?

One of my students did a very interesting analysis of seasonal migration. This is the situation—someone in the household will go to a city, sometimes pretty far away, and work for several months, usually between Diwali and Holi. They work on construction sites, or as security guards, that kind of work. There are instances of an entire family migrating, but it’s rare in this landscape.

The analysis revealed something very interesting about the link between seasonal migration and the climate, mainly the amount of rainfall during really dry years—the poorest of the poor, the lowest income strata, they do this seasonal migration, no matter what. Families with higher income levels (now, this is not a high income level, just a relatively higher one) respond to the climate, the dry years, and migrate more during dry years. So, we see that climate link for those slightly better off. But the very lowest income strata, they have to enagage in this migration, dry, wet, no matter what.

We always say, the poorest are the most vulnerable. Well, they are vulnerable, really, because they are poor.

Research and on-ground surveys suggest that a large incentive to grow commercial rice in the region is because of the minimum support price, and guaranteed procurement from the government. But sometimes, if it's a dry year, some farmers won’t plant anything, and some might plant a variety of different crops because something might grow. There is no clear answer as to what drives these decisions, and climate is just one of them. Photos by Satvik Parashar.

What kind of system wouldn’t model the Green Revolution, but, in some ways, balance sustainable land use while centering people’s needs? I know this is a difficult question, because it is a question of imagination, but you could go wherever you want to with it.

Well, that’s a really great question. The pendulum has swung so far in the direction of incentivising rice and wheat. Of course, we don’t want the pendulum to swing all the way back in the other direction. I think the goal, or the imagination, as you said, is having options, and different markets that are appropriate in different places. And I think the issue of water kind of forces this, because if there’s no water available, how are you going to grow these water-demanding crops?

What makes society, agriculture, and everything resilient is diversity. Having diversity of types of millets, diversity with rice and wheat, and within each of these species, that’s what is essential. Also, in terms of diet and nutrition, what we need is diversity. I would never say that, you know—that rice should not be grown at all, that would be crazy! And what we’ve seen (in trends over time) is that it’s diversity that is declining.

The issue of water kind of forces this, because if there's no water available, how are going to grow these water-demanding crops?

In the past, there’s been so much focus on yield—varieties that produce more—as opposed to looking at a range of traits like being drought-tolerant, salinity-tolerant, pest-tolerant. I think there is now a recognition of how important it is to have this genetic diversity (and I know this is going to sound so dramatic, but it’s true) available to humanity for the future.

But I also don’t want to over-romanticise millets. There is a lot of drudgery involved with these small millets, so one of the things we’re working on is trying to get technology to enter these landscapes to reduce that drudgery.

I really want to emphasise this—if millets are going to become a part of people’s diets, then farmers have to get real benefit from growing them. They have to have the right technology, the right access to markets and the right setup. Right now, they don’t.

Manasa is a legal consultant based out of Amsterdam, specialising in the impact of climate change through a human rights lens. She is a voracious eater, foodie, and cook, and is trying to incorporate sustainability into her food practices.

Mukta heads the Editorial Lab at the Millet Revival Project. She is a writer and editor who works on stories that spotlight the intricacies of our food systems, and how they interact with the climate emergency, the environment, and people.

This article is part of the Millet Revival Project 2023, The Locavore’s modest attempt to demystify cooking with millets, and learn the impact that it has on our ecology. This initiative, in association with Rainmatter Foundation, aims to facilitate the gradual incorporation of millets into our diets, as well as create a space for meaningful conversation and engagement so that we can tap into the resilience of millets while also rediscovering its taste.

Rainmatter Foundation is a non-profit organisation that supports organisations and projects for climate action, a healthier environment, and livelihoods associated with them. The foundation and The Locavore have co-created this Millet Revival Project for a millet-climate outreach campaign for urban consumers. To learn more about the foundation and the other organisations they support, click here.