The self-sufficient hamlets in Tamil Nadu’s Sittilingi Valley offer valuable lessons in taking ownership of community health and farming, and the place millet cultivation occupies in doing so.

Surrounded by dense green forests and cut across by idyllic streams, Sittilingi is a quiet valley nestled amongst the Kalrayan and Sitteri Hills of Tamil Nadu’s Western Ghat range. The Sittilingi panchayat, spread across about 300 hectares of land, is located in the Dharmapuri district, and comprises 42 hamlets with a population of approximately 17,000.

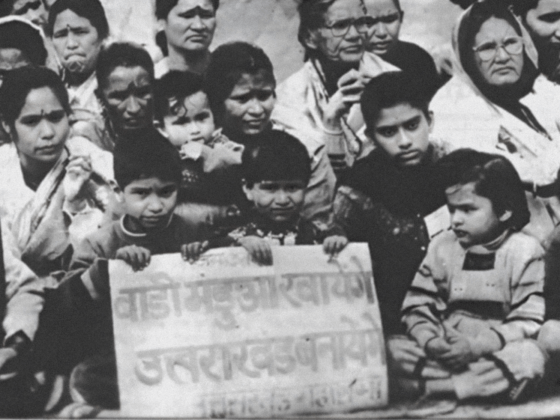

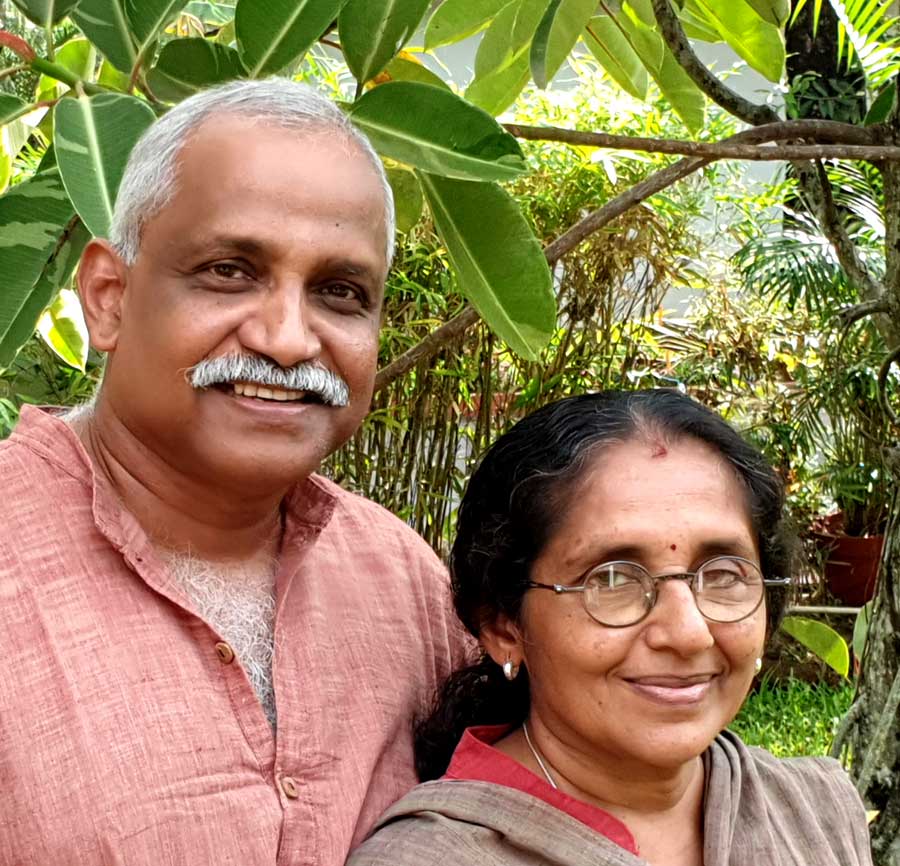

Until the early 2000s, Sittilingi Valley’s island-like remoteness was further accentuated by a lack of access to healthcare and infrastructure, including roads and an uninterrupted supply of electricity. Until 1993, the nearest hospital was in Harur, the sub-district headquarters, about 48 kilometres away. It was during this time that a young doctor-couple, Dr. Lalitha Regi and Dr. Regi George, moved to Sittilingi and set up the Tribal Health Initiative (THI).

What is the Tribal Health Initiative?

The Tribal Health Initiative (THI) began in 1993. Dr. Lalitha Regi and Dr. Regi George were working as doctors in Gandhigram, in Tamil Nadu’s Dindigul district, when they realised access to basic healthcare was one of the biggest hurdles faced by the inhabitants of Sittilingi Valley, which comprises an ethnographic mix of Malayalee Adivasis living in 39 hamlets, the Lambadi community occupying two, and Dalits in one hamlet.

The idea behind THI was to establish a community-based healthcare system wherein selected locals were trained to become nurses and auxiliary health workers. Today, THI has branched out to include organic farming with the Sittilingi Organic Farmers Association (SOFA), a women’s cooperative that aids financial stability, and a crafts collective called Porgai.

Dr. Lalitha recalls that until the early nineties, the hamlets across the Valley were connected by a single road that came in from Kottapatti, the first village outside the Valley. The arrival of the monsoon meant the stream would be flooded, and the road inundated, cutting the Valley off from the rest of the world. “Back then, there would be one bus that operated thrice a day. One had to go to Harur first, then proceed to Salem in a long, roundabout route,” she says.

Following this isolation, community-led interventions in the coming decades that made Sittilingi’s hamlets self-sufficient offer valuable lessons in farming, rural circular economies, and community-oriented healthcare. Over the past 30 years, Sittilingi’s growth and development—one that was propelled by millets for better farming practices and better health—is a journey that is both hopeful and inspiring.

Rooted in traditional cultivation practices, upended by modernisation

It is the summer of 2004. Selvaraj, then a 20-year-old tribal farmer, had just lost rupees 50,000 trying to grow onions on his farm in the Kaliyankottai hamlet of Sittilingi. “We used pesticides and fertilisers. The shoots grew well on the outside but not the bulbs under the soil. It was a huge loss to my family,” he says. That year, Selvaraj was compelled to sell two acres of his farmland to compensate for the losses.

Many farmers, like Selvaraj, were just beginning to go heavy on the use of chemical fertilisers to increase their crop yields. The Valley, owing to its remoteness, almost cut off by the surrounding hills, still held on to tribal agricultural practices—relying on organic fertiliser and practising dry-land farming—well into the late eighties and early nineties, before adopting genetically modified varieties of crops and chemical fertilisers in their fields.

A majority of the population living in Sittilingi belongs to indigenous communities, and most of them cultivate millets. Earlier, villagers grew native varieties of millets like thinai (foxtail millet), ragi (finger millet), samai (little millet), varagu (kodo millet), and kambu (pearl millet) in addition to paddy, pulses, and vegetables. There were varieties within each of these too: Pearl millet comprised pottu kambu (big grains) and naatu kambu (smaller grains), both native varieties. For ragi, there was sigappu ragi (red) and karunchuruttai ragi (black). These native varieties, apart from being highly nutritious, are far more aromatic than hybrids.

The introduction of hybrid varieties of paddy and the use of chemical fertilisers threatened these traditional cultivation practices, whether it was dry-land farming or irrigated agriculture. “The first well was dug out sometime around the early eighties. Until then, people here were used to rain-fed farming,” Dr. Lalitha says. “Multi-cropping was being practised too, but that changed when new methods for cultivating cash crops were adopted.”

“The Green Revolution was just beginning to make an impact in Sittilingi,” says Manjunathan, a field worker with the THI. “Farmers used chemicals for paddy, especially hybrid varieties like IR20. It did not affect us too much but it did have its impact. Our intervention was done at the right time,” he adds.

Manjunathan is referring to the THI pada yatra (journey on foot), undertaken to understand the needs of the local population. “In 2004, we visited all the hamlets [in the Sittlingi Valley]—went door to door and organised small public gatherings,” shares Manjunathan. “We worked from the grassroots level, conducted meetings and discussions with the locals, and only if there was a need for it among people, we worked on it.”

“When we spoke to the farmers during our pada yatra, they did not know how to go back to their old ways, but did feel that their parents’ generation were much healthier,” Dr. Lalitha adds.

The most common problems pointed out by families living in Sittilingi were associated with agriculture. Some were running into debts due to insufficient yields, and the lack of a local marketplace was a definite hurdle. “Farmers had to go to Salem, 70-80 kilometres away. They had to walk long distances, and take multiple modes of transport to reach the commission mandis in Salem. It would take at least two days for them to sell their produce and return. After all the expenses, commission included, they would be left with nothing. Not having local markets was a big problem,” recounts Manjunathan.

They did not know how to go back to their old ways, but did feel that their parents’ generation were much healthier.

Going back to the basics

In 2005, after community discussions, and with encouragement from the team at the THI, a total of four farmers volunteered to give organic farming a shot, Selvaraj being one of them. He set aside 30 percent of his three-acre plot. “Dr. Lalitha suggested that we sow different types of crops in an acre and not just one type. This was useful advice,” says Selvaraj, who has split his farmland among rice, turmeric, mango, plantain, and coconut trees.

“The initial years involved a lot of learning—we began from the basics,” says Manjunathan. This included visiting farms like the Green Foundation in Thali, near Hosur in Karnataka, and meeting farmers practising organic farming in the region, such as Sundarraman in Erode. It was around this time that renowned agricultural scientist and activist G. Nammalvar’s organic farm, Vanagam, was being set up in Karur. Nammalvar visited Sittilingi too, staying for a few weeks and sharing his farming methods.

Selvaraj, who is now 44 years old, remembers these visits from almost two decades ago. “This was very encouraging and helped us trust the process. There was a lot of hesitation and resistance at first. Farmers would attend meetings with us but would not participate in organic farming. Three years later, 30 of them joined us, and the number has only grown,” he says.

The result was the formation of the Sittilingi Organic Farmers Association (SOFA) in 2008, which began selling Sittilingi’s organic produce within known circles. “This is how we started our independent, informal marketing,” Manjunathan says. “We did not tie up with commercial mandis and wanted to bypass intermediates and commissions.”

Prices were fixed by the farmers themselves and they were able to gain 10-15 percent profits, without the need for travel. SOFA first began selling millet grains and turmeric, following which they set up a campus for processing grains into retail products like cookies, flour, porridge mixes, and papads which are sold in larger, local markets and even available online. In addition to selling high-quality turmeric and masala powders, it now also produces and sells soaps and oils. Today, in Sittilingi, about a quarter of farmers have shifted entirely to organic farming, including many large-scale farmers who cultivate between 30 to 60 acres of land. SOFA, too, has grown—its marketing unit becoming more mechanised, and a catalogue of over 42 products that includes sprouted millet flours and health mixes.

“The main point of SOFA was to make sure that the farmers were eating healthy and that they had food security. It was started for the farmers and whatever was extra was sold to the markets,” says Dr. Lalitha. Selvaraj and Manjunathan agree that this has built self-sufficiency over time, while also providing employment to the local youth, who make up almost the entire workforce at SOFA.

Timeline of events

2004 – Pada yatra by Tribal Health Initiative members.

2005 – 4 farmers decide to adopt organic farming on a portion of their land.

2007 – The count goes up to 37 farmers.

2008 – The number reaches 60. SOFA is legally registered under the Society Act.

2015 – SOFA becomes a producer company (Sittilingi Valley Organic Farmers Producer Co Ltd), and starts selling products under the name SVAD (Sittilingi Valley Agricultural Development).

2016 – Annual sales of products reaches rupees 39 lakh.

2023 – Annual sales of products reaches rupees 1.93 crore.

2024 – SOFA has about 700 organic farmers and 500 women who are part of the women’s cooperative.

SOFA’s growth—both financially and in terms of the number of farmers—is not its only victory. As organic farming took off among residents, a women’s cooperative was set up parallelly, to provide more financial support to them. The cooperative plays an important role in supporting SOFA by enabling a stable economy among the local populace.

The cooperative now has about 40 different groups made up of 10-15 women. Meena, who is currently a secretary at SOFA, heads one of these groups. The 53-year-old from Malaithangi hamlet has been a part of this system since 2005. “The biggest benefit of being in groups is financial independence. We save and loan out funds amongst ourselves. Women use the money to invest in livestock, or organic farming, or even for their own personal use. They then sell milk, organic manure, or produce to pay back the loans. This is a well-established chain system,” explains Meena

“Now they have a collective fund of up to rupees 2 crore, which they rotate among themselves. There is no need for bank loans—this is how a circular economy has been set up,” Manjunathan adds. “We are seeing reverse migration because of this.”

The many triumphs of practising organic farming

In 2004, Manjunathan recalls, migration was a major concern in the Sittilingi Valley: local youth would move to places like Chennai, Tiruppur, Kochi, and so forth in search of work. But now, they have ideas for farming-related businesses. The creation of local markets has increased work opportunities for them.

Thirty-eight-year-old Senthil Kumar from Mullikadu village embodies this migration. After working at power looms in Tiruppur for close to 15 years, Senthil moved to Sittilingi to take up farming. “It’s been 10 years since I came back home—I’ve been doing organic farming along with my father,” he says. Senthil’s father is among the initial four farmers from Sittilingi Valley who shifted to organic farming in the early 2000s. “When I was living in Tiruppur, I would buy everything, except water. But now I eat what I cultivate; it is very satisfying. I sell only what’s left above my needs,” he adds.

When I was living in Tiruppur, I would buy everything, except water. But now I eat what I cultivate; it is very satisfying. I sell only what’s left above my needs.

The challenges that millet cultivation brings up still persist. Its harvests are not substantial, and compared to other cash crops, the grains are not very profitable. “But the fact remains that it is very good for one’s health and should never be compared to wealth generation,” Manjunathan says. What THI and SOFA have shown is that processing millets into products locally can help sustain long-term interest and focus on cultivation.

Dr. Regi George verifies that the overall health of people in Sittilingi has improved over the years, augmented by consuming organically cultivated produce. “From when we started in the early nineties to the present day, we can say malnutrition and anaemia are no longer prevalent among the majority of people here. It is one of the reasons we encourage people to adopt organic farming methods and to continue growing millets.”

Anjana Shekar is an independent writer and translator from Chennai. She has previously written on food, cinema, culture, arts, history, and the environment. Her writings have appeared in The Hindu, The News Minute, The South First, and Scroll.in. She also translates short stories from Tamil to English.

Men were conspicuously absent in most of the murals. Where were they? Why were only women shown labouring in the fields, picking leaves, frolicking with lambs, carrying the harvest, or gracing the walls in their traditional attire?

This article is part of the Millet Revival Project, The Locavore’s modest attempt to demystify cooking with millets, and learn the impact that it has on our ecology. This initiative, in association with Rainmatter Foundation, aims to facilitate the gradual incorporation of millets into our diets, as well as create a space for meaningful conversation and engagement so that we can tap into the resilience of millets while also rediscovering its taste.

Rainmatter Foundation is a non-profit organisation that supports organisations and projects for climate action, a healthier environment, and livelihoods associated with them. The foundation and The Locavore have co-created this Millet Revival Project for a millet-climate outreach campaign for urban consumers. To learn more about the foundation and the other organisations they support, click here.