Walking Dehradun’s streets, Somya Dhuliya watched murals depicting Uttarakhand’s fields, farmers, and foods blossom on newly whitewashed walls. But does employing food to create a state’s distinct identity take on an insidious character if the state itself is organised along exclusivist lines?

In 2023, Dehradun started getting a remarkable facelift. Artists commissioned by the Mussoorie Dehradun Development Authority (MDDA) began painting the city’s walls with extensive murals depicting Uttarakhand’s cultural identity—a pastoral idyll with mountains, rolling green fields, and the state’s abundant agricultural bounty.

From Rajpur Road to the Jolly Grant Airport, from Ballupur Chowk to Sahastradhara, I was greeted with scenes out of a rural haven, populated by women adorned with multicoloured headscarves, nathnis (nose rings) and gulobands (traditional chokers). In places, these perpetually smiling women picked tea leaves, in others, they were captured mid-celebration as they danced in their ripe, golden fields. Walking through the city you couldn’t be faulted if you thought perhaps that this is where Uttarakhand lives—in its villages and farmlands, these women its custodians.

I watched these scenes come to life on newly whitewashed walls as I travelled up and down the city. I was gathering ethnographic data for a self-directed research project, which sought to interrogate the state’s gastrodiplomatic industry ( i.e., concerted state-backed efforts that utilise a region’s foodways for economic and diplomatic ends) and its employment of vegetarianism as a unique identifier for Uttarakhand’s foodscape.

I realised the choice of these images was not value-free. Ever since the state’s inception in November 2000, the project of constructing a distinct Uttarakhandi or Pahadi identity has been underway. These murals are a part of the effort—one can glean that this retrospective construction of the state’s cultural identity is tied to its rural spaces, its farms and fields, its produce as being distinct and specific to the region.

Millets are at the forefront of this project, tying the state’s identity to its foodscape. In December 2023, Uttarakhand received a record 18 Geographical Indication (GI) tags in one day with jhangora (barnyard millet) and mandua or choon (finger millet) being two of the recently GI-tagged foods. The GI tag is a way to assure that an item (grain, textile, handicraft) is of a specific geographical origin and has a peculiar character or quality through this origin. This act of tagging essentially emplaces the grains. They’re not just millets, they’re Uttarakhandi millets, intrinsically tied to the geography and cultural landscape of the state.

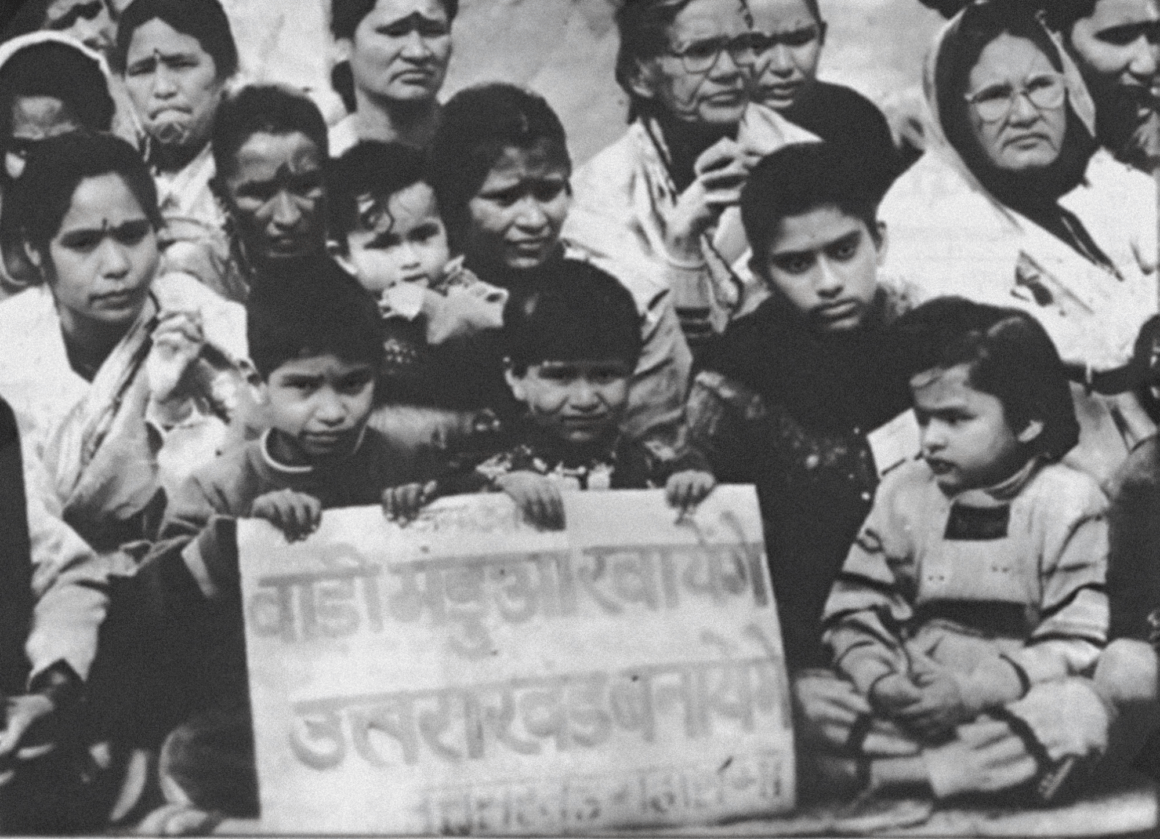

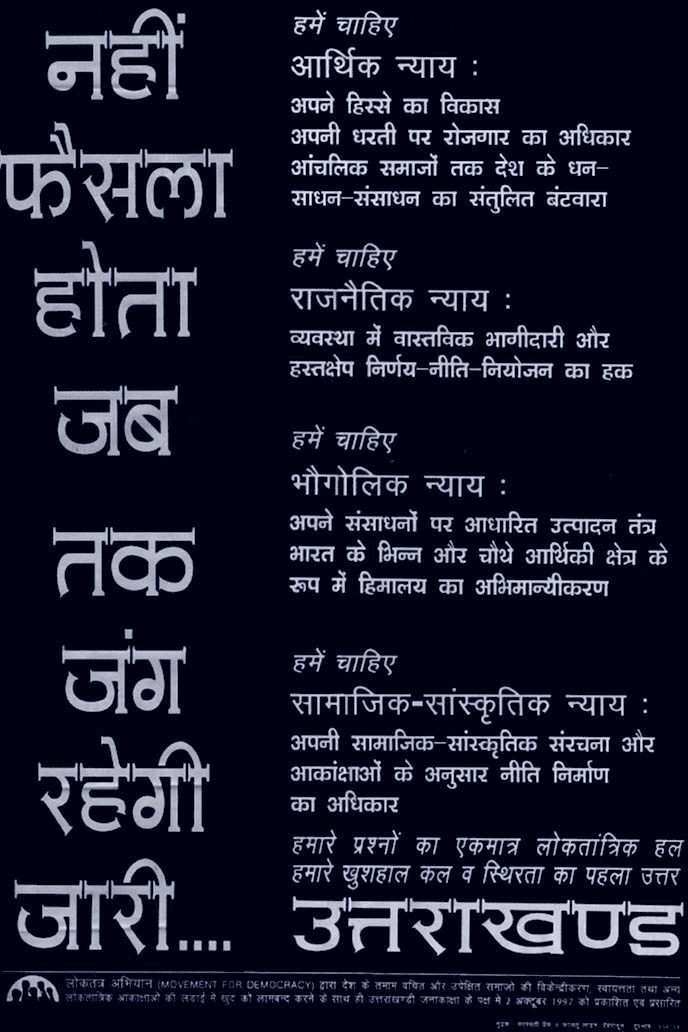

Ironically, this contemporary emplacement feels cyclical, since not very long ago, these millets were being invoked during protests for Uttarakhand’s statehood. In the poster (featured above), statehood agitators are demanding the creation of the state of Uttarakhand with the call for eating mandua, and building Uttarakhand—Baadi mandua khayenge, Uttarakhand banayenge.

They're not just millets, they're Uttarakhandi millets, intrinsically tied to the geography and cultural landscape of the state.

This image caught my eye because it staged the movement’s demands along alimentary lines, making acts of eating and political reconfiguration linked and causal. This is not new. Scholars like Arjun Appadurai, Igor Cusack, Jeffrey Pilcher, and Richard Wilk have elaborated on the centrality of food to the process of nation-making and the use of food as a tool to establish regional and communal boundaries. To me, the poster was reminiscent of scholar Parama Roy’s proclamation in her seminal work Alimentary Tracts—on colonial and postcolonial gastropolitics in the subcontinent—which stated that the “…alimentary habitus, one that included not just the mouth but also skin, sinew, and gut, was the banal yet crisis-ridden theater for staging questions central to encounter and rule…”. Interestingly, this specific call for statehood from three decades ago echoed the state’s fixation on millets today, further thickening the p(l)ot.

I wondered about the place of millets in my own kitchen, and their instrumentality in creating what I, an oppressor-caste Pahadi, perceive as a distinct regional identity. Even though the starches on my plate are now constituted overwhelmingly of rice and wheat, jhangora and mandua featured heavily, especially during the winter months—when crumbling millet flatbreads were served with dollops of ghee or cooked into sticky balls to scoop up hearty, leafy gravies.

Growing up in Dehradun in the 2000s, my circle consisted of mostly non-Pahadi friends. The city came to grow around its schools and educational institutions, attracting settlers from a wide range of backgrounds in newly independent India. Pahadi migrants from rural hilly areas settled here much later, my own family having arrived in the 1980s. Most of my friends were strangers to choon ki roti, jhangore ki kheer, or phaanu-baadi (horsegram curry with baadi). Even if I hadn’t been cognisant of it earlier, millets being a part of our kitchen had always been a point of both difference and identification for me.

I soon corroborated this, through my research project, with ethnographic accounts of oppressor-caste Garhwali Hindus whom I interviewed to find out about their eating practices. While speaking to a mix of rural and migrated urban dwellers, my questions started in the same place: What did you grow up eating? What, according to you, constituted Pahadi cuisine? Every interviewee started their answer with jhangora, mandua, buransh syrup (made from rhododendron flowers), and bhatt ki daal (black soybean).

Shilpa¹, from Pauri-Garhwal, spoke of eating millets throughout her childhood, with gora anaj (wheat and rice) being prized cereals saved for special occasions. Migrating to Dehradun meant a sharp decline in her intake of millets as fair-price shops stocked just the usual cereals. However, in the last decade or so she had noted a resurgence of millets in her diet, driven by growing awareness of their health benefits and their increasing demand and availability in urban centres.

Mahesh, also from Pauri-Garhwal, identified mandua and jhangora as key ingredients in any Pahadi kitchen and seemed ecstatic about their increased popularity, which, to him, was a sign of the world catching up to healthy, traditional Pahadi kitchen regimens. Laced with dietetic advice about the grains’ glycemic index and anti-inflammatory properties was a strong identification of their consumption with a distinct ‘Pahadi-ness’.

In 2023, the state government launched the State Millet Mission. The aim was to provide subsidies on seeds, and to address issues of market linkages as well as a lack of primary processing in order to ensure better availability of crops grown by rural, Pahadi farmers for the general consumer. This mission also benefits from related initiatives to bring a greater agricultural area under organic farming in the state, such as the Traditional Agricultural Development Scheme and the Namami Gange initiative. And the incentives for growing millets through changes at the policy level seems to be bearing fruit!

As a recent study by IIM-Kashipur reported, the centre and the state’s efforts have increased the annual income of 75 percent of millet farmers of Uttarakhand by 10-20 percent. A traditional grain, inextricable from the gastronomic cartography of a region, displaced from plates due to interventions that privileged wheat and rice, has now found its way back onto plates. There might be a long way to go, but perhaps we’re on the right path? Perhaps the sloganeer was onto something—there existed an undeniable bond between the consumption of millets and the drawing of the political and cultural boundaries of Uttarakhand.

A State is Born

But whose Uttarakhand is it? Let’s go back to the slogan, the state’s conception, and the context against which the calls for statehood gained momentum. Uttarakhand was carved out of Uttar Pradesh in 2000, following a drawn-out statehood agitation movement. Though a demand for a separate state of Uttarakhand had been simmering in the hills for decades, the movement gained traction, and grew out of the anti-affirmative action protests of the late 1990s.

These protests were prompted by the Mulayam Singh Yadav-led Uttar Pradesh government’s decision to implement the recommendations made by the Mandal Commission in March 1994—a 27 percent reservation in the government seats for members of oppressed castes. This was unacceptable to the oppressor caste population in the hills, who erupted against the decision, alleging that the oppressed caste population in the Pahadi region at the time was 2-3 percent and that the implementation of this reservation would harm the socio-economic fabric of the region. Some scholars have tried to contest these claims, but the lived experience of the Dalit population in the region says otherwise. From casteist calls to posters calling for the rights of the people to determine their social constitution, Uttarakhand’s birth was steeped in a casteist hysteria emboldened by the entrenched systems of caste oppression in the region.

These attitudes shape and inform state policy, turning Uttarakhand into a veritable “savarnocracy”, as Mahesh C. Donia writes in The Caravan, with both de facto and de jure observation of the caste system. Millets, historically associated with marginality, food insecurity, and Dalit kitchens in the subcontinent, are not exempt from this political organisation. The state’s millet mission, while ostensibly addressing issues of procurement, processing, and transportation, fails to account for the systemic challenges faced by Dalit farmers in the region. Small landholdings, contractual farming, inadequate irrigation, the intensification of extreme weather events due to climate change further compounded by escalating human-animal conflict caused by the loss of forest cover, all contribute to the precarious conditions under which Dalit farmers labour. Since no appropriate considerations are made to address these issues where they start, the recent millet-based policies work to widen gaps that already exist.

Millets, historically associated with marginality, food insecurity, and Dalit kitchens in the subcontinent, are not exempt from this political organisation. The state’s millet mission, while ostensibly addressing issues of procurement, processing, and transportation, fails to account for the systemic challenges faced by Dalit farmers in the region.

Director Nirmal Chander’s documentary Moti Bagh (2019) provides some insights into these dynamics. The film follows Vidyadutt Sharma, a poet, farmer, and activist, as he struggles against the forces of outmigration and political apathy to sustain the agricultural landscape of his village in Pauri-Garhwal by tending to his five-acre farm with the help of his farmhand Ram Singh, a Nepali migrant. Early in the film, Sharma, an oppressor caste figurehead, attends the wedding of an oppressed caste couple in the village, to give them his blessings. Not much later, he comments, “The communities we thought are low caste and of no value, they are the ones keeping the mountains alive. In villages where Scheduled Castes live today, some life still remains. All those who called themselves upper castes have migrated. If Uttarakhand looks deserted, it’s all because the upper castes ran away. It’s my belief those who stand with you in difficult times are truly your family!”

Seemingly well-meaning, the statement underscores how caste privilege shapes who gets to leave for the (less) green urban pastures and who stays back to shoulder the burdens of farming. Migration then becomes not merely an economic choice, but one deeply informed by caste. Dalit communities in Uttarakhand are tethered to the land by systemic inequities. Sharma’s paternalistic observation is evidence of the irony of the state’s agricultural survival resting disproportionately on the shoulders of those historically marginalised within its social order.

Whose State Is It Anyway?

It is impossible to get a sense of these inequalities from the pastoral scenes adorning Dehradun’s walls. These murals act as an aesthetic gloss over the grim realities of agricultural production in the hills, erasing Dalit and migrant labour and the hierarchies that underpin it. As I watched the murals crop up across the city, what was missing became just as revealing as what was depicted.

Men were conspicuously absent in most of the murals. Where were they? Why were only women shown labouring in the fields, picking leaves, frolicking with lambs, carrying the harvest, or gracing the walls in their traditional attire?

This absence is no accident—a systemic erasure that mirrors lived realities of rural Uttarakhand, where the feminisation of farm labour has intensified due to outmigration. Men increasingly leave to seek better-paying opportunities in urban areas, creating a crisis that leaves women to bear the full weight of agricultural responsibilities alongside unpaid domestic duties.

Dalit women, in particular, endure the harshest burdens of this shift. Positioned at the intersection of caste- and gender-based oppression, they face limited access to resources, work in precarious conditions, and are also vulnerable to exploitation. The murals, with their sanitised and picturesque portrayals, invisibilise these struggles, presenting instead an idealised tableau that distances the viewer from the realities of rural life. The extent of this erasure is evident in the reclamation of millets among oppressor caste Pahadis I interviewed, and my own ignorance that turned them into an axis of culinary identity without consideration for the people who cultivate them and the circumstances in which they do so.

When I began writing this, I set about to walk the city again, this time to document the murals I had only observed earlier. For my last stop, I turned onto Curzon Road. Facing the entrance of a senior secondary school was a mural depicting a young girl bending down to touch the feet of a man loaded with Brahmanical caste markers. Next to this was a woman in a field, a scythe in hand as she made her way through ripened ears of brown-beaded inflorescence—unmistakably ragi, mandua, choon. The sense of uneasiness and shame I felt looking at the juxtaposition of these murals, is hard to describe.

Back home, my mother is preparing Choon Mandi—a light, sour preparation made with ragi flour and buttermilk. It is frequently made in the winter as it warms the body. She roasts the flour and sets it aside, then places a pot full of buttermilk on the stove. Once it reaches a low boil, she adds in the flour, whisking it quickly to avoid any lumps.

As it cooks slowly—about 20 minutes—the kitchen is filled with a tart scent that fights for attention with the pungent aroma of chillies, cumin, garlic, and salt being ground on the sil-batta. This quick batch of Pisa Loond, or flavoured salt, is our sole seasoning for the meal. We help ourselves to large servings, mix in a sinful amount of the loond, and sip the scalding, flavourful soup under the winter sun till we’re content, and, more often than not, primed for a nap.

But right then, it is impossible to disassociate this food from the multiple complicities it is caught in. Yes, the fact that millets are climate-resilient make them exceptionally well-suited to the agroecological needs of the hour, while their health benefits address growing health concerns of a burgeoning urban populace. But any efforts in this direction would be insufficient if they do not address existing inequalities. How does an uncomplicated tying of these millets to Uttarakhand’s identity obscure oppression—both historical and ongoing—and who gets a say in the construction of this cultural identity?

Why does the construction of this identity rest upon images of marginal(ised) bodies that obscure their very marginalisation?

¹ Name changed upon request. These interviews involved questions about the eating practices of oppressor-caste Hindus in Uttarakhand, as well as questions about meat consumption. Since the issue of animal sacrifice was brought up, many participants opted to remain anonymous.

Somya Dhuliya is an Editorial Lab Volunteer at the Millet Revival Project. Having completed her Master’s in English Literature from Jamia Millia Islamia, she is spending her days reading, writing, and researching in the field of critical food studies. You can find her on Instagram at @roundthemulberrybush.

This article is part of the Millet Revival Project, The Locavore’s modest attempt to demystify cooking with millets, and learn the impact that it has on our ecology. This initiative, in association with Rainmatter Foundation, aims to facilitate the gradual incorporation of millets into our diets, as well as create a space for meaningful conversation and engagement so that we can tap into the resilience of millets while also rediscovering its taste.

Rainmatter Foundation is a non-profit organisation that supports organisations and projects for climate action, a healthier environment, and livelihoods associated with them. The foundation and The Locavore have co-created this Millet Revival Project for a millet-climate outreach campaign for urban consumers. To learn more about the foundation and the other organisations they support, click here.