A fermented, porridge-like ragi drink offers more than just succour on a hot summer’s day. For most communities in Tamil Nadu, it is a means of sustenance. For Valli, it tastes best when had with leftover fish curry.

She buys the ragi whole, which often comes strewn with dust and stone particles. She washes it twice, dries it with a cotton cloth, lays it out in the sun for a day or two. Dried well, she spreads the ragi on her moram, a winnowing mat; she tosses the grain up and sideways into the air. The stones, heavier, fall to one side, to be discarded. The next day, she walks a little less than a kilometre to a rice mill nearby, to get the ragi ground into flour. Women from the neighbourhood bring their own ingredients—wheat, dried spices like red chillies or turmeric—ensuring a store of cost-effective, flavourful, and preservative-free kitchen essentials.

Valli doesn’t remember the first time she drank koozh, or the day she learned how to make it. Growing up, she watched her mother make it always, and drank it often. What she does remember is that the fermented millet porridge, made with kelvaragu (ragi), was easy, comforting.

“Do you drink koozh often?” I ask, meaning, “Still, even now?”

“Almost everyday,” Valli replies, which means making it at least twice a week for her family of three: her two sons, aged 19 and 21, and herself.

Valli is an informal worker living in Porur, Chennai. For innumerable working women like her—who cannot afford to spend much time in the kitchen, yet want to make nutritious meals for their families—koozh has a large presence in the home kitchen.

It is evening, the setting sun gives way to darkness, as I watch her prepare the ragi flour—the first step in making koozh. She simply adds water to the flour, until the water is about half an inch above the flour. There are no measuring cups, or hesitation, in how much of each she adds to the large vessel. She stirs the mixture together with her hands, initiating fermentation. Now, it will rest on the counter until the next day.

Valli wakes up at 4.30 am every day. She is employed as a domestic worker at three houses; one of them, mine. She sweeps and washes the front porch around all the houses and draws a kolam—geometric patterns made with rice flour—on the floors.

She lives two kilometres away from me, and has invited me home many times in the last three years. But it is only now, when I want to learn about her koozh, that I take her up on the offer. Her house is on a road I cross frequently but never look away from. It is a pastel pink outside, ocean blue inside. There is a line of flowering plants along the squat compound wall.

From 9 am to 6 pm, Valli also works as a labourer at a construction site. “The good thing about working at construction sites is I don’t have to go every day,” she tells me, relieved. The pay is rupees 700 a day, and though she needs the money—there are medical loans, bus fares, rent to pay—she took a break through most of May. It is unbearably hot. “The koozh helps cool us down,” she says.

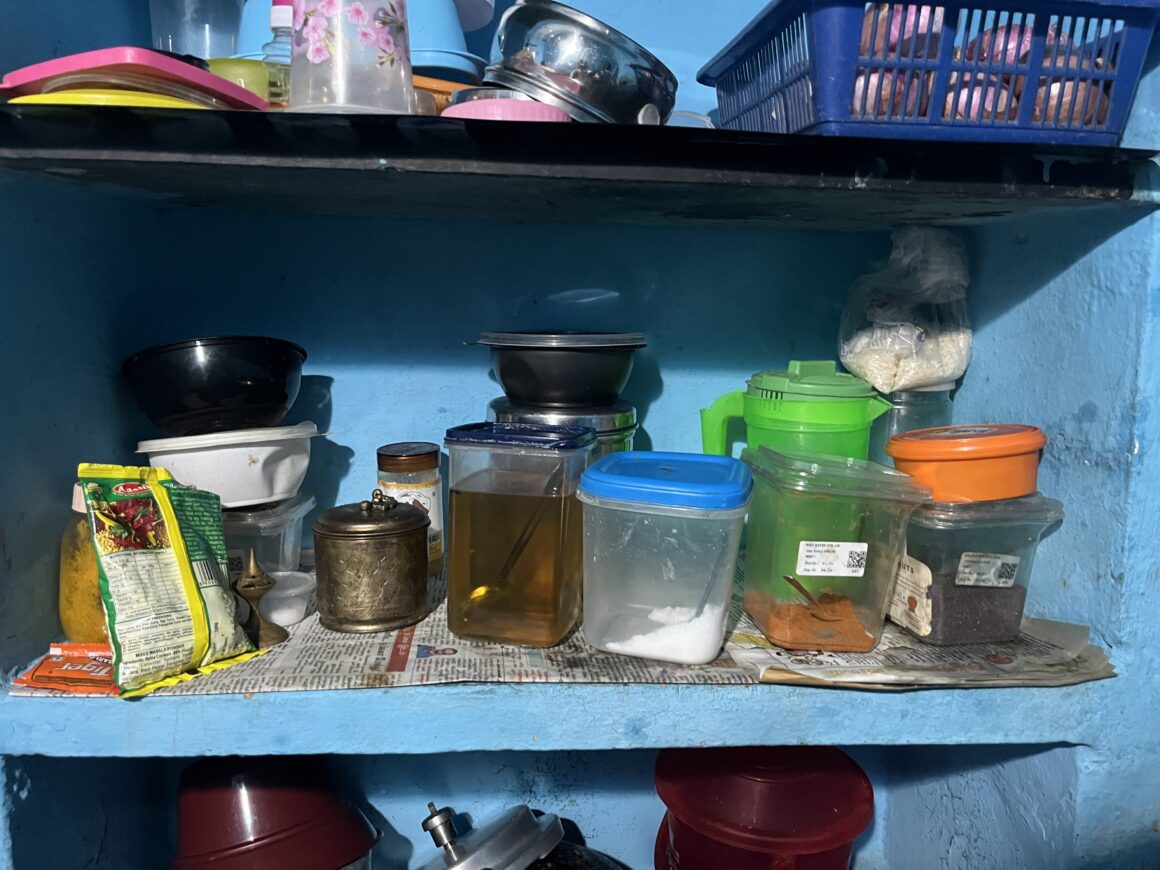

The many colours and flavours that characterise Valli’s home.

By the next evening, the ragi flour has been fermenting for 24 hours.

Valli’s cat Pattu hasn’t returned from her afternoon scavenge, but her three kittens are napping. Today we don’t stop in her hall to chat—we have koozh to make. It is sweltering, and Valli suggests we make it quickly and get out of the kitchen. She has already prepared the noi arisi (broken rice) by boiling half a kilogram of it in water in the morning, then refrigerating it so it doesn’t ferment in the heat.

I watch her prepare the ragi flour—the first step in making koozh. She simply adds water to the flour, until the water is about half an inch above the flour. There are no measuring cups, or hesitation, in how much of each she adds to the large vessel.

She boils the noi arisi for about ten minutes, until it reaches a rolling boil. While it boils, she mixes the fermented ragi flour well with her hands until it is runny. She slowly adds the ragi to the noi arisi, stirring continuously until both are combined. The mixture continues to cook for 20-30 minutes, stirred intermittently.

The two building blocks of koozh—fermented ragi flour and cooked rice. Upon fermenting, the ragi batter appears foamy. While idlis, dosas, and pongal are quintessential Tamil breakfast fare, kanji and koozh is where it really begins.

I ask her how her day went. “Like every other day,” she responds matter-of-factly. Just as when she says she still eats koozh regularly. Or when she says she might move soon, to a house in a parallel lane, where the rent is half of this one. This one, which has a hall, a bedroom, and her small kitchen.

Despite its vague geographical and cultural origins, koozh has a stronghold within the Tamil community, especially its agrarian one. So does kanji, which is any porridge in the region, really. They are often had as standalone meals, devised as they were on the basis of need—keeping sustenance, well-being, and the availability of locally abundant millets (like kambu and kelvaragu) in mind. While one can trace the origins of foods like idli and dosa, kanji and koozh have a more ubiquitous provenance and presence. There is no particular community or region to trace back to.

Koozh is synonymous with summer. It can be had with pearl onions, pickles, curries, even sliced raw mango. At times, a sweet unfermented version is offered as prasadam in some temples during July and August.

Perhaps this is what has kept the humble drink alive even as the population of farming communities has diminished in the region. It continues to be consumed in both rural and urban areas, especially by those whose work involves intense physical labour in the scorching sun. As Valli mentions, the drink has a cooling effect on the body, apart from other nutritional benefits. Most importantly, though it might indicate a lack of choice or wealth when it comes to food, it does taste good.

Come summer, koozh is everywhere. Most cities in Tamil Nadu, including the metropolitan Chennai, have push carts lining busy roads—serving koozh and buttermilk—run by women making the drink at home in large batches. It is mixed with buttermilk to further elevate its refreshing effect, and served with chopped onions, colourful poppadoms, and pickle. The accompaniments are endless.

Most importantly, though it might indicate a lack of choice or wealth when it comes to food, it does taste good.

Auto drivers and food delivery partners often throng these carts, looking for respite from the unforgiving heatwaves most cities in Tamil Nadu have faced this season. One sombu of koozh (a mid-sized metal drinking pot) costs around rupees 35, an economical option for a sustaining meal for most daily-wage labourers.

“It tastes like earth, with a little bit of tartness,” Valli tells me. You can have it with whatever you like; it would taste just as good. “My favourite is to have it with leftover fish curry.”

Throvnica Chandrasekar is a writer and editor based in Chennai, exploring stories around indigeneity and environmental inequality. She was previously a storytelling intern at The Locavore.

This article is part of the Millet Revival Project 2023, The Locavore’s modest attempt to demystify cooking with millets, and learn the impact that it has on our ecology. This initiative, in association with Rainmatter Foundation, aims to facilitate the gradual incorporation of millets into our diets, as well as create a space for meaningful conversation and engagement so that we can tap into the resilience of millets while also rediscovering its taste.

Rainmatter Foundation is a non-profit organisation that supports organisations and projects for climate action, a healthier environment, and livelihoods associated with them. The foundation and The Locavore have co-created this Millet Revival Project for a millet-climate outreach campaign for urban consumers. To learn more about the foundation and the other organisations they support, click here.