How do botany and archaeology come together to reveal mysteries of our past agrarian life? What role do millets play in this? Mukta Patil speaks to archaeobotanist Dr. Dorian Fuller to find out why he loves to sift through the daily rubbish of old settlement sites, and what we can unearth from the past to build the future.

I’m always fascinated with things that don’t instantly connect with each other because it feels so much like putting a puzzle together. What could the early (and oh-so-aromatic) trade in frankincense and myrrh have to do with sorghum? Did the idli originate in the Neolithic period in southern India? Why did a particularly enigmatic millet called raishan remain cloistered in the Khasi hills of Meghalaya, while kodo spread across the Indian subcontinent? Archaeobotany, which is the science of recovery and study of preserved plant remains from archaeological sites, can help us piece all these things together.

Archaeobotany tries to find what people, historically, used plants for—food, fuel, medicine, or rituals. Things that we used routinely, like remains of grain crops, seeds, or nutshells tend to get preserved, and we can learn so much about what our lives might have been like through these remains! Dr. Fuller’s work focuses on understanding how the staple crops we eat have evolved and travelled, and he is particularly interested in understanding the origins, importance, and evolution of millets.

Edited excerpts from our interview with Dr. Fuller:

What can archaeobotany tell us?

What the archaeobotanist does is try to recover (the often very fragmentary) plant remains from ancient contexts, identify them, and therefore be able to say something about the environment and the plant use of people in the past. Archaeobotany is very good at getting at agricultural staples and core elements of the diet.

Where do you find archaeobotanical remains?

Some archaeologists study standing monuments like temples, or sculptures. Others might excavate ancient burials. Neither of those are particularly good places to find archaeobotanical evidence. We’re interested in basically the daily rubbish from settlement sites, so places where you have the remains of houses, storage pits, or fireplaces. Places where people are living routinely, and producing household waste, or cooking, so the fires around will lead to the preservation of plant remains.

And then those plant remains get mixed in with the sediment. We have better preservation on sites that have multiple layers—which means they are long lived, usually permanent sites. We have much less information about hunter gatherers, generally, because their sites are often much more ephemeral. But once we get into the agricultural period, people tend to leave behind plant material. We have archaeobotanical evidence on agricultural sites, pretty much everywhere, once we start to look for it.

What is the role of millets in early agriculture, and why haven’t we really looked into it as much as other grains?

Archaeologists, just like everyone else, are biased by what they already know. Millets were under-studied partly because they were less important in agriculture in places like Europe, where people were setting the research agendas.

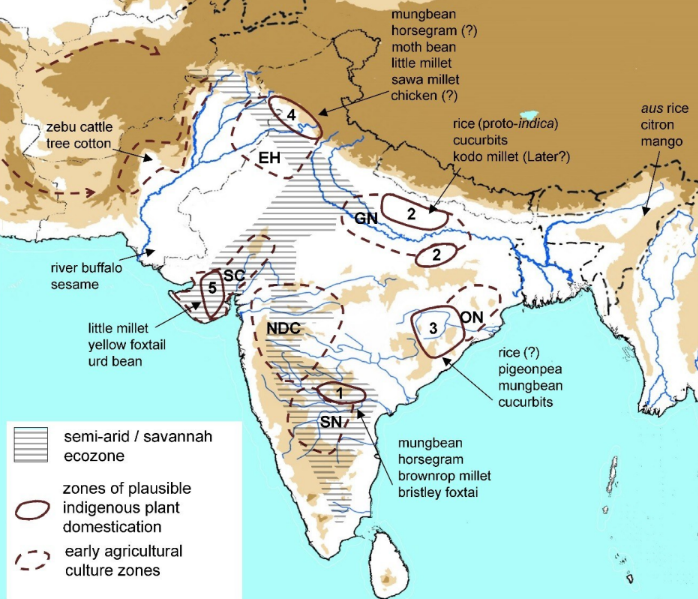

The parts of the world where millets are the foundations for early agriculture include Africa (western and eastern Africa), northern China, and India. We tend to know more about the millets of Chinese origin, and that’s because there’s been a lot of investment in archaeological research in China, and also because the common foxtail millet spread out of China and reached Europe in the Bronze Age. So it turns up in European archaeobotanical samples.

There’s also a number of different species of millets. They are often superficially similar, but significantly different. So there’s also a challenge of being able to identify the archaeological remains correctly.

How does your work address this gap?

A lot of my research has really focused on India and Africa because these are the regions which are really underrepresented in archaeobotanical research; we know much less about domestication processes here. When I started my PhD research in 1996-97, in South India, it was clear to me that this was a centre where you have wild ancestors of the mung bean, and probably horse gram. And it was also a centre for the traditional cultivation of a diversity of millets, some of which are native to India, but we didn’t really know much about them.

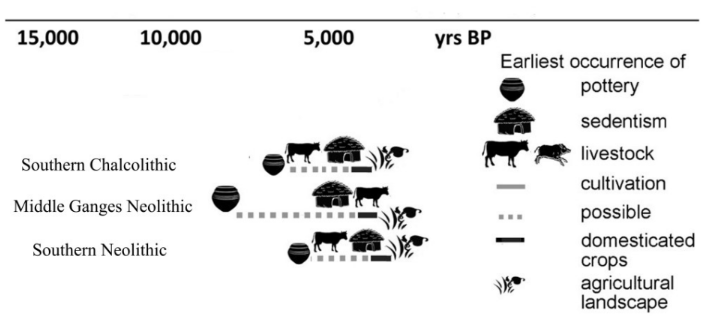

What my research showed is that in the Neolithic of South India, so 4000 years ago, and probably starting a bit earlier, the dominant cereal staple was browntop millet (Brachiaria ramosa). And that was one that wasn’t written about in books on crop domestication, or the origins of agriculture.

What does your work help us to understand about crop domestication and millet cultivation practices in South India? What kind of story can we tell about that period, and the people?

We can say some things about each, and there’s more work to be done on both.

In the South Indian Neolithic sites, often the larger sites are on granite hilltops. People were elevated above the plane, and they had a nice view of the landscape. At that time, cattle pastoralism was very important. And that means a large portion of society and each community was probably seasonally mobile, to take advantage of different forage and watering sites.

Near the village site, the crops that dominate the record in the southern Neolithic are browntop millet (Brachiaria ramosa), but then it’s grown alongside mung beans and horse gram, in particular. We also have some evidence for toor dal (pigeon pea), but that’s more limited. We have a second small millet, which is bristly foxtail (Setaria verticillata). At present, it’s unclear whether that’s a domesticated species or a tolerated companion of browntop millet, but we think they’re harvesting and processing it nonetheless.

So the settlers have a diet that includes pulses and millet. They also have stone tools for pulverising and making flour. So it’s very likely that they are dry roasting pulses and pulverising it into flour and mixing that with millet flour. In tools for processing, they have cooking pots that they could be boiling or steaming things in.

Of course they are keeping cattle in large numbers, also sheep and goats. They are eating some meat—we know that from butchered bones. It’s likely that they’re using dairy products as well. So we have to imagine that the millet is part of a cuisine in which legumes are very important, but also animal products like dairy.

Over time, their diet diversifies. They also adopt, throughout this period, wheat and barley. Wheats and barley were the staple foods in the Indus Valley, in the Harappan civilization. About 1500 BC, we start to get evidence of some crops of African origin—a little bit of pearl millet on a few sites, the occasional sorghum. We also get hyacinth bean (lablab) which turns up in large quantities.

Bajra and jowar, which are very important today, started to become important maybe 1500 to 2000 years ago, even if they were introduced 3000 or 3500 years ago. It took a very long time for them to displace the traditional millets.

Wheats and barley were the staple foods in the Indus Valley, in the Harappan civilization. About 1500 BC, we start to get evidence of some crops of African origin—a little bit of pearl millet on a few sites, the occasional sorghum. We also get hyacinth bean (lablab) which turns up in large quantities.

What is the journey of any millet, from being a wild grass to being domesticated?

What happens with cereal domestication (and this is true of even wheats, barley, and rice) is that there are a number of changes that occur gradually, taking a few thousand years, which differentiate the domesticated millet from its wild ancestor.

In the wild, millets are grasses, and grasses produce seeds or grains, held in the husk and a spikelet. And once that’s mature, it shatters and falls off the mother plant, into the soil. That creates a shift in the reproductive cycle from one where the millet reproduces itself, and sheds its seed by shattering, to one in which it reproduces itself, and humans harvest and plant the seeds.

Millets also evolved larger grains—so grains got fatter, rounder, plumper. We can see that by measuring archaeological grains, like pearl millet in West Africa, and both the North Chinese millets. This takes a long time, three or four thousand years!

Another change that takes place is increasing seed numbers. If you compare the number of grains on a wild millet, whether it’s foxtail or browntop, to those on a domesticated species, there’s more grain per plant. After they’re domesticated, plants also tend to become taller, and more compact, so you can fit more plants per field.

Could you tell me which millets we can now identify as indigenous to India? What are some interesting things we don’t know about their evolution?

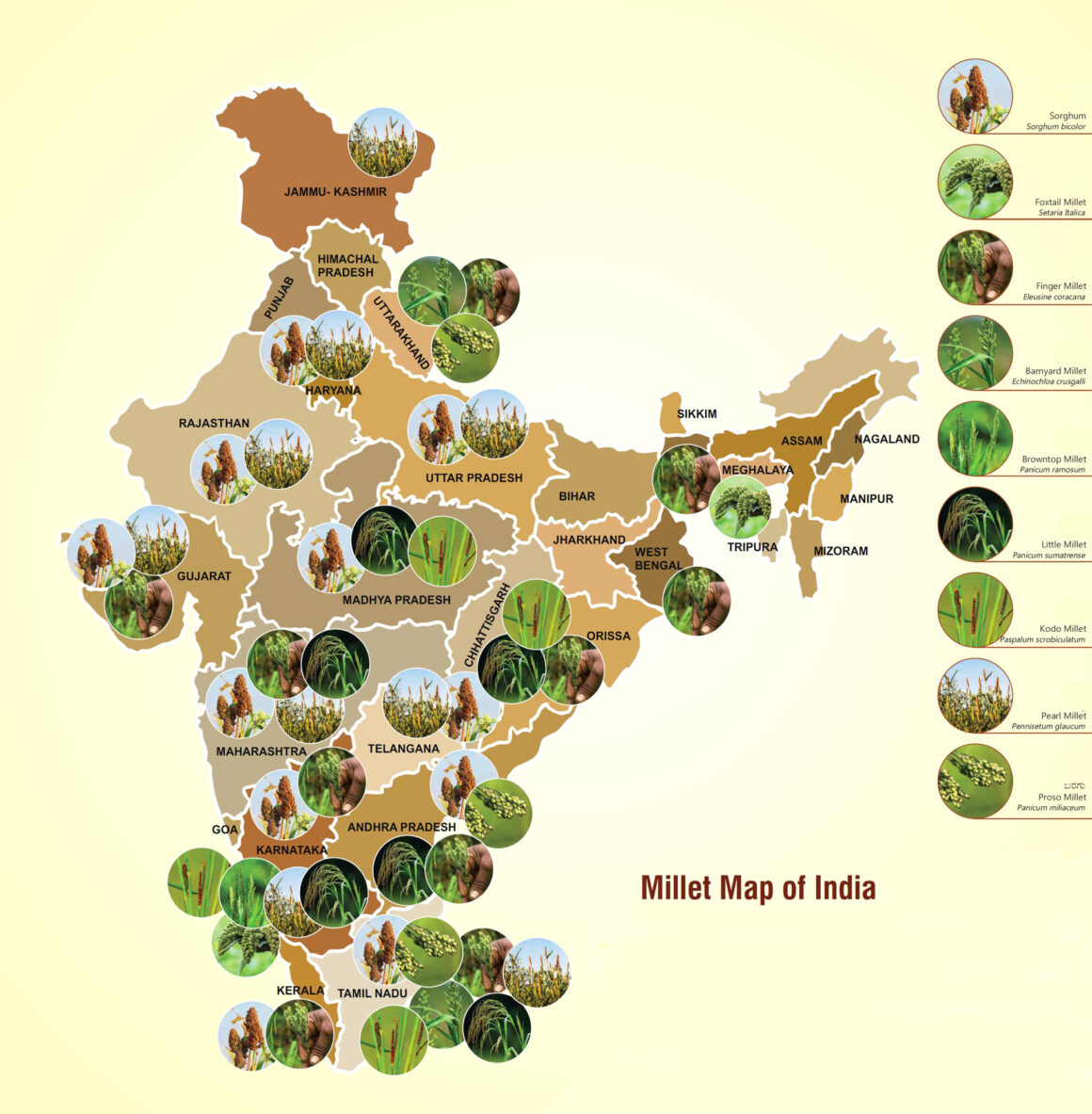

We can work out the millets that are indigenous based on who their closest wild relatives are. India really has a diversity of millets in its history, and its agricultural diversity.

Browntop millet (Brachiaria ramosa), Indian little millet (Panicum sumatrense), and Indian barnyard millet (Echinochloa frumentacea), these are all clearly indigenous. Then, there’s minor ones, like the bristly foxtail (Setaria verticillata), which turns up on a lot of sites in South India, archaeologically. It seems to have been a cultivar in the past, even if it isn’t anymore. And you have another foxtail millet, the yellow foxtail (Setaria pumila). It’s cultivated as a minor millet in parts of Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra in recent times, but is also archaeologically present in Saurashtra.

Also kodo millet (Paspalum scrobiculatum). And that’s a different kind of a story! Kodo millet, we think, evolved as a weed of rice cultivation in North India. In the Ganges plains, in Odisha, there was early rice agriculture. So it is probably first spreading as a weed of rice, but it can do very well under drought conditions, when the rice doesn’t.

In the Northeast, you have a fascinating millet, raishan (Digitaria cruciata). It is grown among the Khasi tribe in Meghalaya. We know very little about its history, and it seems to be endemic and indigenous to that region only. And that’s an interesting crop in that, in western Africa, there’s a number of minor endemic millets that are called the fonio millets. The main fonio is Digitaria exilis, and it is very important in places like Senegal, Ghana, and parts of Mali.

Fonios are the cousins of the same genus as raishan. There has been a parallel evolution of these Digitaria millets in Northeast India, and parts of western Africa.

Why do some millets stay local, and others not?

Well, that’s a very good question. There is a geographical factor—that’s where that species was wild. So that’s where it was first cultivated and domesticated. I suppose the question you’re asking, which is a more difficult one, is why did it remain limited to that region and not spread elsewhere? I’m quite fascinated by why some crops go through a globalisation process, and others remain local. I don’t have a good explanation.

If you look at the spread of kodo, once it’s domesticated from a weed of rice, it spreads throughout India and Sri Lanka, and east into parts of Myanmar. It spreads quite widely, but not much beyond the Indian subcontinent.

Crops like pearl millet spread throughout Africa and India, so they have a very wide distribution. And then you have crops like raishan, which, as far as we can tell, remains in the Khasi hills of Meghalaya. And that’s it, it never really spreads anywhere.

Now, some of that may be because we don’t really have good archaeological evidence from that part of the world; maybe it was more widespread in the past than it is today. It may be about ecological tolerance. The ability for crops to move is also connected to trade patterns and trade networks. In places that are more isolated from trade, things are less likely to disperse.

And it may also be about how they’re perceived in terms of culinary potential at the time, how they fit into cooking patterns. Because when people encounter a crop, if they’re told, ‘Oh, this is how it’s cooked where it comes from’, and that’s a cooking method they don’t use, then they might be wary of trying it.

The ability for crops to move is also connected to trade patterns and trade networks. In places that are more isolated from trade, things are less likely to disperse.

Is there something particular about India that makes it a hotbed for a variety of millets?

India has a high diversity of environments, in terms of climatic zones and vegetation, from deserts like the Thar, from the semi-arid, dry grasslands in the central Deccan, outwards towards moist and tropical rainforests in the Western Ghats.

But then in those areas, you also have the potential for different cultural groups, not necessarily in contact with each other, to hit on the notion of cultivating millets. They don’t necessarily start with the same millet, and so you have a diversity of places, millets, and also groups.

The other part of the world that has a relatively high diversity of millets is western Africa. You have pearl millet, the fonios, and the adoption of sorghum. In a sense, that is similar, in that you have a series of belts of vegetation, from tropical rainforests in the south, through the savannas, up to the Sahara desert in the north, where you have relative close proximity of these different climatic and biogeographic zones.

How did some of the millets that did travel far, move from Africa and arrive in India?

In some ways, that’s a mystery! They had to have arrived by boat because there’s no evidence for any of these African species in Egypt or the Middle East, so they didn’t go over land. They came through what we think of as the Arabian Sea trade.

The zones in which sorghum was domesticated and cultivated (the Sahelian and Northern Savanna zone in Africa) extends east, through what is today modern Eritrea, right to the Red Sea coast. At the time, a Red Sea trade industry is established.

At the same time, we know that there’s also a major trading sphere in the Persian Gulf, between Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq) and the Indus Valley, especially during the period of the Indus civilisation. There’s regular trade between Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley, and some of the Harappan ports are in places like Gujarat, on the Saurashtran peninsula. And that trade was very active from 2500 BC to 1900 BC during the Harappan civilisation.

I think what happens, some time towards the end of that period (around 4000 years ago), is a linking together of the Red Sea trading world and the Persian Gulf trading world, through Arabian coastal societies, who are doing a lot of fishing. And so you start to have the potential for things to move from Africa, via this trading network, to Saurashtra.

The Saurashtran peninsula is another area which has very early millet agriculture. Here the staple grain seems to be the Indian little millet (Panicum sumatrense). I think African crops are adopted in Saurashtra, as minor things to try out alongside native staples. Once they’re in India, they travel through trade networks within India and make their way to South India.

It’s not a direct trade from Karnataka to Sudan—it’s a down the line trade where little bits of grains are being moved alongside other things like incense, obsidian, and textiles.

But, there is a certain amount of speculation here, and guesswork!

What can we learn from millet cultivation practices of the past, that we can take into a future where we are facing so much uncertainty? In terms of erratic monsoons, climate change, soil erosion, and even malnutrition and hunger?

If you look at agricultural modernisation (which maybe starts in the 19th century), it tended to promote monocropping, heavy investment in chemical fertilisers, in herbicides and pesticides, and mechanisation. They are underpinned by heavy fossil fuel, and lead to long periods where soils are barren, which leads to erosion and loss of natural nutrients. It went for simplification and scale over sustainability.

Agriculture, in the past, was much more local, though maybe more labour-intensive. It relied on the natural complementarity of multiple crops, and was integrated with systems of livestock management. If you grow a number of millets, and oil seeds and pulses together, they help each other. They’re harvested at slightly different times, it requires people to be out there, but it exposes the soil less, and requires less herbicide and pesticide because you grow the right species together.

If we go back to the south Deccan, one of the interesting patterns we see is in the earlier part of the Neolithic—there were big piles of cattle dung that had been burned (what we call ashmounds). And those declined through the course of the Neolithic, and by the end, disappeared. As people become more agricultural, more invested in browntop millet and other crops, that cattle dung becomes more and more of an agricultural resource. And that’s quite important to think about.

So I would say the next revolution is about moving back to diversity in agriculture, and agriculture that’s more local.

Mukta Patil heads the Editorial Lab at the Millet Revival Project. She is a writer and editor who works on stories that spotlight the intricacies of our food systems, and how they interact with the climate emergency, the environment, and people.

Image credits:

(a) Photo by Cmhenkel (CC BY-SA 4.0). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

(b) Left, David von Diemar. Right, Sergio Camalich. Courtesy of Unsplash.

(c) Left, Zde (CC BY-SA 4.0) . Centre, GeoTrinity (CC BY 3.0). Right, Snotch (Public domain). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

(d) Photo by Vidishaprakash, CC BY-SA 3.0. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

This article is part of the Millet Revival Project 2023, The Locavore’s modest attempt to demystify cooking with millets, and learn the impact that it has on our ecology. This initiative, in association with Rainmatter Foundation, aims to facilitate the gradual incorporation of millets into our diets, as well as create a space for meaningful conversation and engagement so that we can tap into the resilience of millets while also rediscovering its taste.

Rainmatter Foundation is a non-profit organisation that supports organisations and projects for climate action, a healthier environment, and livelihoods associated with them. The foundation and The Locavore have co-created this Millet Revival Project for a millet-climate outreach campaign for urban consumers. To learn more about the foundation and the other organisations they support, click here.