In parts of West Bengal, millets are mainly grown today for the purpose of making eu or millet wine, finds Bengt G Karlsson.

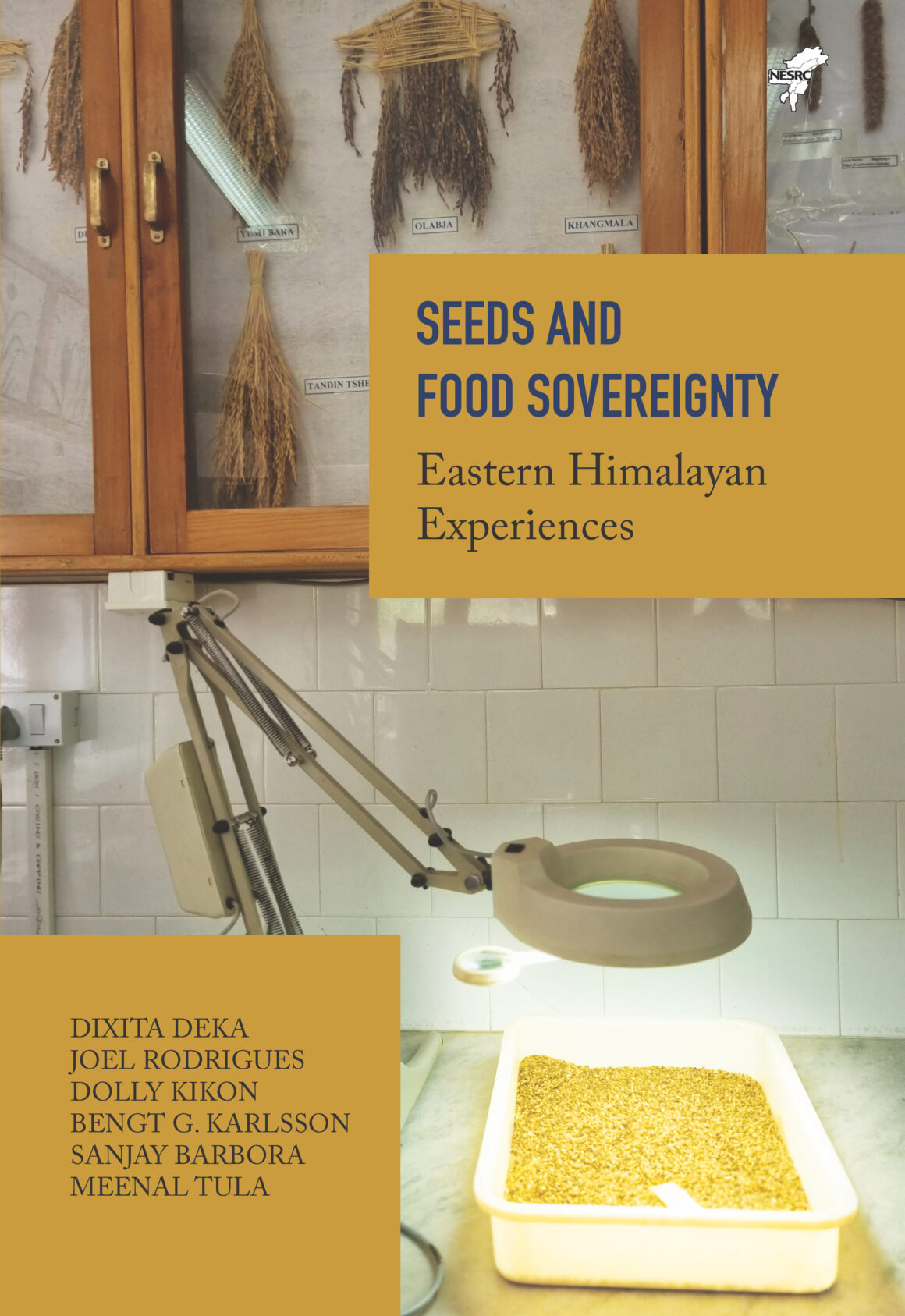

Bringing together farmers, activists, knowledge keepers and students, Seeds and Food Sovereignty: Eastern Himalayan Experiences was a result of attempting to facilitate new ways of learning together. Published by North Eastern Social Research Centre (2023), it draws attention to the commodification of seeds, the need for local seed banks, and captures the stories of community custodians of food and indigenous food practitioners.

In this chapter, Bengt G Karlsson, a professor of Social Anthropology, looks at how millet is grown in North Bengal and Sikkim, and what it means for the people who grow it.

Read an excerpt from a chapter titled ‘Chasing Millets in North Bengal and Sikkim’ by Bengt G Karlsson:

“They are replanting the millet seedlings in Totopara now, you must come,” my friend Krishnapriyo told me over phone from Siliguri. A few days later, we are on our way to the village located in the northern most part of Alipurduar district in West Bengal. Totopara sits at the border of Bhutan and the banks of the mighty Torsa River to the east. Persistent rains make the journey difficult as rivers and streams commonly overflow and make passage impossible for days at stretch. However, this time we were lucky and our jeep could reach without problems.

Our first stop was the home of Doniram Toto, development officer and prominent intellectual, who often acts as the spokesperson for the community. Doniram explains that during his grandparents’ time the Totos practised shifting cultivation (Jongkung-wa), but they gradually gave it up after independence. Millets and maize are the main food crops for the community, but the former have been on a steady decline over the last few decades.

Nowadays, as we learned during our stay, millets are mainly grown for the purpose of making eu or millet wine. Eu, people kept telling us, is a necessity for all pujas or whenever people get together to celebrate. Yet, as Lapsi Toto, an elderly woman, explained, “The future of millet is bleak. But it has to be preserved; how otherwise will we be able to hold weddings? The problem is that people are turning to areca nut as it is much more profitable.”

And indeed, areca nut groves are coming up everywhere. The hill sides, all the way to Bhutan, are covered with areca palms. Agricultural plots in the village that earlier cultivated millets and maize now have young areca palms growing.

Rita Toto, the first Toto graduate, now working as development officer, explained that elephants are making farming increasingly difficult. Elephants are especially fond of maize and it is hard to chase them away from the fields, she explained further. As villagers are turning away from cultivation of food crops, they depend more on food from the market and the monthly rations of rice and wheat provided for free through the Public Distribution System.

The future of millet is bleak. But it has to be preserved; how otherwise will we be able to hold weddings?

Many among the young are engaged in salaried work outside the village and have little interest in farming. This might also explain the switch from food crops to less labour-intensive areca nut cultivation.

The Toto story, however, is more complicated than a straightforward transition from subsistence agriculture to cash crop farming. The Totos were earlier known for their oranges. Once upon a time, the hills around the village were covered with orange trees rather than areca palms. Oranges were traded for paddy and the Totos also carried oranges from growers in Bhutan to buyers in the Bengal plains. The demise of the orange economy remains unclear; nobody could really explain why and when it happened.

In the Survey and Settlement report of 1895, Sunder writes that all the orange trees in Totopara had died. According to late anthropologists B K Roy Burman, who carried out long-term fieldwork among the Totos in the 1950s, the orange trade was finally discarded in the 1940s as part of an agrarian transition to settled, plough agriculture. Roy Burman mentions that the women in the village lamented the transition as they had become dependent on men for ploughing the fields.

I was in Totopara to chase millets, but now I kept thinking about oranges. What happened to the orange trees? Could suddenly all the areca palms be wiped out in a similar manner? A PhD student from North Bengal University conducting fieldwork in Totopara told me that you can find a few scattered orange trees in the surrounding forests. And apparently, the Totos still celebrate a special puja to the deity of oranges.

I was in Totopara to chase millets, but now I kept thinking about oranges. What happened to the orange trees? Could suddenly all the areca palms be wiped out in a similar manner?

Along with Doniram, we rushed to the site where the millet action was happening. About 25 to 30 men and women of different ages were busy taking up seedlings from a seedbed, wrapping these together in bunches, and carrying these to a larger field above. There, another team quickly replanted the seedlings in freshly prepared soil. The mood was high and everyone seemed to be enjoying the collective work.

As we learned, they were taking turns working on each others’ land. On that day, they were working on land belonging to an elderly woman. I asked the owner what kind of millets she cultivated, a question that turned into a larger discussion among those gathered regarding different millets’ varieties. The finer details of the discussion escaped me, being lost in translation between Bengali, Toto, and English.

Yet, it was clear that most farmers today preferred finger millets (kodo or marva, in Bengali), which was considered especially suitable for the making of eu. As I later enjoyed a few glasses of the fermented beverage, I could confirm that the taste was indeed lovely.

This is an excerpt from Seed Sovereignty: Eastern Himalayan Experiences (2023), published by North Eastern Social Research Centre. Read more about the book here, which can be accessed for free.