What makes Odisha Millets Mission (OMM) stand out in a sea of other government programmes? The Locavore learns about how women Self-Help Groups are championing millets, and the inclusion of ragi ladoos in Anganwadi meals.

As we look at bringing millets back into our kitchens and finding ways to spotlight them, it’s important to acknowledge the role of initiatives like Odisha Millets Mission (OMM) in championing millets. A flagship programme of the government of Odisha, OMM was launched in 2017 to improve the nutrition of tribal communities in Odisha through revival of millets in farming and their diets.

Some of their approaches to revive millets have been hugely effective, like introducing millets in the Public Distribution System (PDS) and Midday Meals—both of which impact vulnerable communities. What’s also remarkable is that farmers are at the center of the work they do, which matters so much when it comes to any aspect of growing food.

As we work on the Millet Revival Project 2023, we are grateful to be able to learn from the gathered knowledge of interventions like OMM and WASSAN (Watershed Support Services and Activities Network), which has played a crucial role in designing and implementing OMM.

Excerpts from our interview with Aashima Chaudhary, Program Manager at WASSAN:

The Odisha Millets Mission is seen today as a kind of model for others to adopt—especially state governments—owing to its success and impact. What do you think have been the biggest strengths of the programme?

Odisha Millets Mission (OMM) is a uniquely designed, government-facilitated multi-stakeholder intervention with a ‘fork to farm’ approach. It focuses on developing a sustainable food system of millets, and ensuring nutritional security for vulnerable farmers in the rainfed areas of Odisha. OMM has been instrumental in creating an enabling ecosystem for better production, developing a millet value chain, campaigning for behaviour change, and increasing household consumption of millets.

Most importantly, OMM is a people’s programme. Farmers take centrestage, and are directly involved. There is community ownership. There is an NGO network. And this is essential for millets, which are not just about a value chain, but also a value system. The state government has adopted a societal approach to institutional commitment and coordination under OMM.

Millets are very much in the spotlight today. Since this is officially the International Year of Millets, what are your hopes for it? What is the one thing that we should get right?

The Government of India (GoI) is making a concerted effort—both domestically and abroad—to boost the production and consumption of millets. Once known as ‘coarse grain’ (mota anaz), millets have now emerged as nutri-cereals as they are loaded with micronutrients, minerals, amino acids, protein, and fibre.

In Odisha, OMM is revalorising these nutri-cereals, which were fast fading away from the agricultural landscape. The state government is focusing on these humble crops to regain its value on the plate. However, following a silver bullet solution will not help mainstream millets. There is a need for a more holistic and inclusive approach to ensure that farmers get a fair price. Our government should provide Minimum Support Price for all minor millets, too, instead of for just a few major millets.

Millets are a blessing for small-scale farmers facing climate change, suffering from poverty, and failing to get adequate nutrition. Millets should be included in their regular diet—shifting consumer preference is key. Behavioural change campaigns, enabling policies, and investments are needed to bring millet back into people’s diet.

OMM has developed the standards for millet processing and value-added machinery, and set up decentralised processing machinery at panchayat and block levels that are operated and managed by women self-help groups and farmers producer organisations. Such decentralised and people-centric approaches have created livelihood opportunities. More research and development are needed to develop efficient machinery for millet that can work in energy-constrained rural areas.

Civil society organisations can play an enabling role in helping the government to combat malnutrition by introducing millets in Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS). Introducing unpolished millets locally in ICDS, Midday Meals, and PDS to replace a proportion of rice or wheat can stimulate demand, production and investments in millet value chains.

While there’s a lot of focus right now on consuming millet, there isn’t as much attention being given to those who grow millets. What does the buzz around millets mean for farmers?

This is true. There has to be a balance in the investment between both. As much as we have to work on awareness and create access for urban consumers, one has to work with farmers for them to be able to grow millets back, have enough support systems, offer training for better agronomic practices, and so on.

Right now, organised and structured work with farmers to increase production and productivity of millets is in small clusters and limited scope. GoI, state governments, and agriculture departments should start schemes to support farmers. It is important to create better livelihood for farmers, especially rainfed farmers. Dedicated resources for this from public institutions is important.

Are millets easier for farmers to grow than, say, rice and wheat? And what are the millets that are being grown as part of Odisha’s Millet Mission?

Millets are low-duty, and low-input intensive crops. They consume 70 per cent less water than rice, grow in half the time as wheat, and require 40 per cent less energy in processing. Besides, millets are pest-resilient, and have a long shelf life.

Under the Odisha Millets Mission programme, farmers are supported to grow finger millet (ragi), little millet, foxtail millet, kodo, and bajra. To enhance productivity, OMM has promoted improved agronomic practices such as System of Millet Intensification (SMI), Line Transplanting (LT) and Line Sowing (LS) with diversified millet crops. These methods are working well in Odisha. The average yield of ragi has increased by more than double in the last four years, from an average of 6 quintas to 14 quintals per hectare.

Odisha has now included millets in Anganwadis for preschool students as part of the State Nutrition Programme. How is it cooked for children, and what has the response been?

Odisha has introduced millet-based food in the state nutrition programme in Keonjhar and Sundargarh districts. Ragi ladoo is universalised under Integrated Child Development Services in Keonjhar and Sundargarh district, covering 1.5 lakh pre-school children in 6,077 Anganwadi centres as an additional supplement in morning snacks. Ragi ladoo mix is highly nutritious—rich in iron and calcium that enhances growth in children.

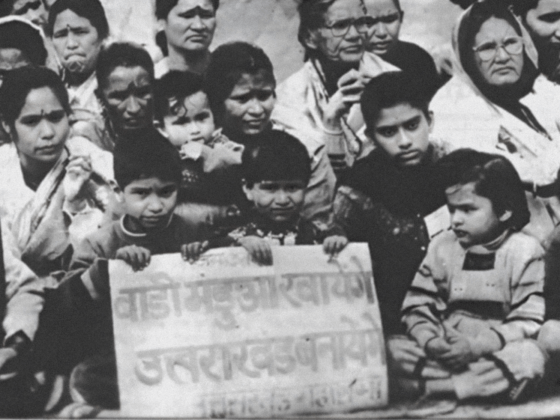

During the covid-19 induced lockdown, when the Anganwadi centres were closed to follow covid protocols, ragi ladoo mixed flour was distributed as take-home ration among the parents of preschool children. Additionally, the initiative provides income to women self-help groups. Women self-help groups are involved in preparing the ragi ladoo mix, and supplying it to the local Anganwadis. Tribal women play an instrumental role in introducing millets-based recipes to meals of school children, to fight malnutrition and ensure dietary diversity among preschool children.

Ragi ladoo is universalised under Integrated Child Development Services in Keonjhar and Sundargarh district, covering 1.5 lakh pre-school children in 6,077 Anganwadi centres as an additional supplement in morning snacks.

The response to such millet based food has been overwhelming at different fronts. Preschool children happily eat ragi ladoo at Anganwadi centres, while their parents reported that their food culture stays intact by including millets in the children’s diet.

Tapping the nutritional values of millets could be a potential low-cost, pragmatic strategy to enhance the nutrition intake in tribal areas. This has increased dietary diversity and nutritional gains, and also revived the age-old traditional culture of millet consumption in the tribal areas. Niti Aayog has presented the ragi ladoo programme of Sundargarh and Keonjhar district as part of the best practices in the country under diversification of take-home ration products.

How are millets typically used in food in Odisha? Which millets are popular?

Odisha is one of the most culturally diverse states in the country. The state is home to 62 tribal communities, including 13 Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups, which constitute 23 per cent of the total population. For these communities, millets are a major staple, closely associated with their cultural and heritage agricultural systems.

The tribes celebrate the harvest of millers en-masse, and offer different types of millet dishes, such as mandia ladoo, Khiri, manda pitha, khichdi, and jau, to their deities. Various types of millets—finger, foxtail, kodo, pearl, little, and jowar among them—have been traditionally grown in different parts of Odisha. The tribal communities consider millets one of their principal crops as they thrive in their soil, local climate, and ecology, and can withstand climate changes.

With the support of OMM, women self-help groups are leading a revolution through their millet-based food enterprises, such as Millet Shakti Tiffin Centre, Millet Shakti Cafe, and Millet Shakti Outlet. These groups have introduced a wide variety of millet recipes, blending traditional Odia and modern cuisines. Some of the popular millet recipes prepared and sold by the self-help groups running Millet Shakti Tiffin Centre include pakoda, samosa, jalebi, idli, vada, kheer and kakare made with ragi and little millet.

Similarly, Millet Shakti Cafe offers biscuits, mixture, khurma, rose cake, and ladoo made from eight grain varieties, including ragi flour, sorghum flour, and little and barnyard millets. And in the Millet Shakti Outlet, a range of packaged millet food items is available, such as ragi and sorghum flour, ragi cookies, ragi ladoos and ragi mixture, and khurma and muduki.

With the support of OMM, women self-help groups are leading a revolution through their millet-based food enterprises, such as Millet Shakti Tiffin Centre, Millet Shakti Cafe, and Millet Shakti Outlet.

What does the demand-supply chain look like in India at the moment? With the current push for consuming more millets, will the supply be able to meet our demands?

Right now, supply is more than the actual demand. People have just started eating millets again, but it is not very regular in their diet. Supply and demand shall have to be managed as there is a lot of opportunity to grow and consume millets. More than 55 per cent of the cultivated area in the country is under rainfed agriculture, and with increasing climate change, even more area is likely to be most suitable for millet cultivation. With improved agronomic practices, yields have increased. In India, it will likely take us over a decade to reach the overall demand and supply of millets that we’re aspiring to.

As more people in India consume millets, what would you like them to keep in mind?

While millets are full of benefits and adding these wonder grains to your lifestyle can prevent many chronic diseases, you must gradually introduce millets to the diet.

Millets contain phytic acid, an anti-nutrient that could reduce the absorption of other nutrients. But soaking, sprouting, or fermenting millets will break down the anti-nutrient, and reduce its negative effects. The high fibre content of millets and, therefore, slow digestibility may cause havoc with the gut in some people, especially those with intestinal disorders.

So it’s important to observe how one does on millets before adopting the grain in large quantities, or as a substitute for wheat or rice. It’s best to start with the lighter grains, like ragi and foxtail millets, and then move onto a variety that includes jowar and bajra. Millets are a good source of amino acids, but very high levels of amino acids can be harmful to the body.

Including the right food ingredients with millet recipes will ensure good bioavailability. For instance, the high calcium content in ragi needs vitamin D to help absorption, and the high iron content in many millets need vitamin C to help the absorption. Similarly, millets consumed should ideally be preservative-free, not chemically processed, and used in their whole grain form. This will enhance the retention of nutrition contents in millets.

This article is part of the Millet Revival Project 2023, The Locavore’s modest attempt to demystify cooking with millets, and learn the impact that it has on our ecology. This initiative, in association with Rainmatter Foundation, aims to facilitate the gradual incorporation of millets into our diets, as well as create a space for meaningful conversation and engagement so that we can tap into the resilience of millets while also rediscovering its taste.

Our thanks to OMM and WASSAN, for coming on board as knowledge partners on the Millet Revival Project 2023.

Rainmatter Foundation is a non-profit organisation that supports organisations and projects for climate action, a healthier environment, and livelihoods associated with them. The foundation and The Locavore have co-created this Millet Revival Project for a millet-climate outreach campaign for urban consumers. To learn more about the foundation and the other organisations they support, click here.